What comes to mind when you think of buildings constructed by the ancient Egyptians? It probably conjures up pyramids or the massive stone temples of the gods. While these are the most obvious architectural structures, they were only the eternal houses of the dead and the gods. Stone architecture, while built to stand the test of time, was simply an imitation in stone of the traditional wattle and daub architecture.

Humans, including all of the kings, lived in much more ephemeral structures-houses made from unfired mudbricks. While they may seem humble, these homes were made of materials and designed in a way that has kept the ancient Egyptians cool without air conditioning for millennia.

Ancient Egyptians and Domestic Architecture

Interest in domestic archaeological sites in Egypt has increased over time. Some of the most famous ones are Deir el-Medina, where the men who built the tombs in the Valley of the Kings lived and Tell el-Amarna, where even the pharaoh Akhenaten lived in a mudbrick palace. From the Greco-Roman period, the village of Karanis is well-preserved.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly NewsletterThe preserved homes of historic Cairo have received more attention in recent years and also show many of the same elements found in their pharaonic predecessors. As recently as two decades ago, if you traveled by train through Upper Egypt, you would have seen homes made of the same material as they would have been made in ancient times, unfired mud brick.

Building with Mud: The Techniques and Advantages of the Ancient Egyptians

Mud may seem like a very poor material to build with, but it offered a number of advantages due to Egypt’s environment and climate. It was readily available, as each year, when the Nile flooded its banks, new silt was laid down that could be turned into bricks. Wood, on the other hand, was relatively scarce and was reserved only for elements like doors and roofs.

The ancient Egyptians built these homes from silt mixed with sand and some sort of chaff such as straw. They mixed the mud with their feet and formed bricks in wooden frames. After they laid out the bricks to dry in the sun, they would have stacked the dried bricks in layers, one on top of the other. Then they spread layers of the same mud mixture between layers to get them to hold together. In order to protect the bricks and provide a smooth surface, the walls are usually plastered with a mixture of mud and chaff, and possibly painted with a lime wash.

Egypt’s climate today is roughly the same as that in ancient Egypt. Most of the year, it is extremely dry and hot. The low humidity along with the lack of rain, meant that mud houses could stand the test of time. Moreover, mud is a poor conductor of heat, so as long as the house was kept closed up during the hotter part of the day, it was less affected by the hot weather outside. Likewise, in the winter, mudbrick homes are warmer.

Ancient Egyptians and Wind Catchers

The ancient Egyptians also took advantage of other climate constants in cooling their homes. When the wind blows in Egypt, it generally comes from the north. This simple climatic fact underpinned navigation on the Nile, with sails unfurled during upstream (southward travel). It also underpinned a common method of cooling homes.

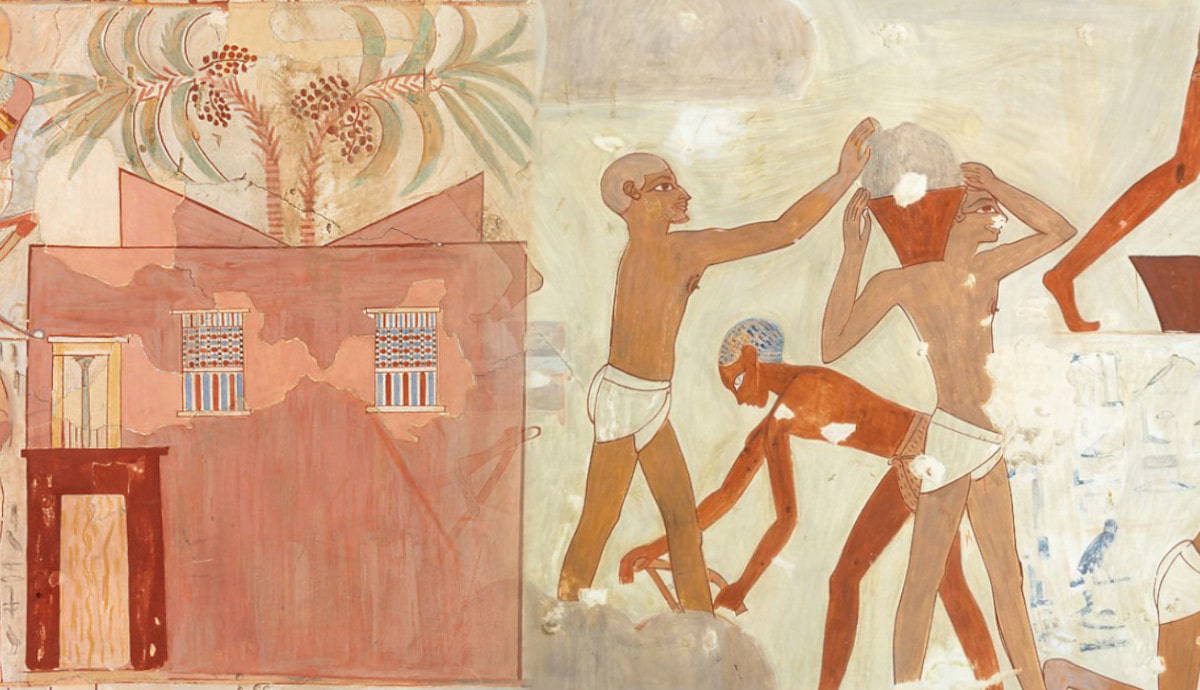

A prominent feature of the ancient Egyptian house that could have helped keep it cool was a structure known in Arabic as a malqaf. While we don’t have any archaeological remains of such structures from pharaonic times, there is a depiction of some on a house in a tomb in Thebes and on a funerary papyrus in the British Museum. They consisted of a triangular-shaped windcatcher on the roof open towards the north, which drew the cooling north breeze down into the house.

The Egyptians seem to have considered this natural air-conditioning method to be one of the most effective ways of cooling for millennia because when Napoleon invaded Egypt over 200 years ago, his artists drew the houses of Cairo, and nearly every single house had one. Several still exist on historical houses you can visit in Cairo today.

Clerestory Windows

Privacy was likely another important consideration in the design of Egyptian houses, so several elements were designed with that in mind on top of climate. Windows in ancient Egyptian houses were usually small and high in the walls, just below the ceiling. While you couldn’t see out or in these windows from the street, they allowed light to enter into rooms during the day, while at the same time providing a way for hot air to rise and escape from the house.

Courtyards

While many ancient Egyptians lived in small, cramped homes, those of the upper classes could afford to build homes with courtyards.

Courtyards not only serve as a shady place to sit away from the blazing sun in the middle of the day, but more importantly, they cool the remainder of the house surrounding the courtyard. When the doors of the surrounding rooms facing the courtyard are left open overnight, hot air rises from the courtyard to be replaced by cool air from above. This air then flows through the doors to the interior parts of the house. During the day, the doors are closed, trapping the cooled air inside.

Courtyards also allowed house residents to engage in activities that generated a lot of heat outdoors, keeping the house interiors cool. Frequently, this included cooking, but even in the working-class areas of Tell el-Amarna, there were shared courtyards between houses where artisans who worked metal and faience producers located their kilns and did their work. Courtyards are also a standard feature in the remaining historic houses of Cairo.

Cooling Drinks

When temperatures climb above 40C or 110F, a cool drink of water is absolutely essential. But how did the Egyptians manage to keep their drinking water from becoming boiling hot in such weather? The answer was clay pots. These pots came in 2 sizes. The zeer is a large pot that stood on a stand and they scooped water out from it with a cup. A smaller personal version is the qulla, which often has a filter on top to regulate the flow of water and keep flies out.

A zeer or a qulla works on the same principle as evaporative coolers. Made of marl clay found in the margins of Egypt’s Nile Valley and then fired, these jars are porous. On hot days, water seeps out to the surface of the pot and evaporates, leaving cool water behind inside. The temperature of the water is pleasantly chilled, but not teeth-chattering cold like water stored in a refrigerator.

Mashrabiya

Another way that houses have been kept cool in Islamic times was using mashrabiya. These wooden screens are made in an intricate lattice pattern. Often oriented toward the prevailing winds just as malqafs were, and covering entire walls, mashrabiya brought cool air into houses while also bringing in light.

The word “mashrabiya” in Arabic literally means the place of drinking, because a zeer or qulla could be placed in front of them, with the breeze rapidly cooling the water inside.

Mashrabiya work is first attested in the medieval period. Because it can take up to 2000 pieces of wood to make a single meter, it would have only been used in the homes of the well-off because of the work involved. However, It also was economical in that it used up small pieces of wood from other work that would have otherwise been discarded.

Mashrabiya were often found in the harem or the part of the house where the women socialized. Located on the second floor, they could see the activities in the courtyard, room, or street below from the openings in the mashrabiya, but could not be seen from outside, protecting their privacy.

The Traditions of Ancient Egyptians Today

The cooling traditions of ancient times have come to be neglected in modern times. With the building of the Aswan and High Dams in Egypt, the silt that was brought down during the annual floods of the Nile was trapped in Lake Nasser. What little was left was needed to keep the fields fertile. Egyptians see fired red brick and cement buildings as higher status than mudbrick and are now the materials of choice for building. Architects no longer incorporate courtyards and malqafs into their plans. As in many countries around the globe, Egyptians have chosen electric fans and air conditioners as the preferred cooling method.

Nonetheless, elsewhere, some of the popular elements of house cooling developed by the ancient Egyptians live on. In many of the Gulf countries, houses are topped with square malqaf towers. Finally, architects incorporated metal mashrabiya into his design of the Institut du Monde Arabe, not for ventilation but to produce a stunning lighting solution.