Behaviorism is a discipline in psychology that suggests that all human and animal behavior is conditioned through interaction with the environment. It systematically studies the observable behavior of humans and animals, ignoring more subjective information such as the thoughts and feelings of the subject.

Behaviorism was a dominant philosophy in mainstream psychology from shortly after the 1913 publication of John B. Watson’s “Psychology as the Behaviourist Views It” until the mid-1950s.

The Scientific Roots of Behaviorism

As early as the seventeenth century, prominent thinker Thomas Hobbes (1650, 1709) expressed an interest in discovering if the stunning advances achieved by science could be applied to the study of human nature. According to Harzem (2006):

“From the renaissance through the age of enlightenment, reasoned decision increasingly acquired primacy over decision by faith or edict in scholarly study and matters of human affairs. The natural corollary of this development was that the sciences, collectively, came to be regarded as the imperative undertaking if dependable solutions were to be found for the problems of human life.”

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

Behaviorists were part of an ambitious push to find methods that produce empirical, objective data that could be reliably collected and adapted to a variety of research tasks (Harzem, 2006). Traditional psychology and the massively influential works of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung placed emphasis on unconscious processes.

Behaviorists conducted experiments geared towards the elimination of the subjective, hoping to yield new insights while bringing psychology into the realm of modern science.

The Main Theories of Behaviorism

John Watson (1913) claimed that humans and animals, exposed repeatedly to an evocative stimulus (e.g. something scary) accompanied by a neutral stimulus (e.g. something uninteresting), would eventually respond the same way to the neutral stimulus alone as they do to the evocative stimulus itself. This became known as classical conditioning – Ivan Pavlov’s experiments on dogs being a famous example.

Edward Lee Thorndike (1927) later claimed that creatures rewarded for some behaviors and punished for others would exhibit more of the rewarded behaviors in the future, in what came to be called operant conditioning. These claims were tested through various experiments conducted on animals and humans in laboratories all over the world. Some of these experiments provided fruitful insights into psychology; others became infamous for the suffering inflicted on test subjects.

Watson believed that his findings could be used to predict the outcomes that certain stimuli, experiences and lifestyles could manifest in an individual’s lifetime. His vision didn’t stop there – he thought that deliberate manipulation of people’s experiences and stimuli could bring about specific, desired outcomes.

“Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I’ll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select—doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and, yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors.” (****)

4 of the Most Famous Behaviorist Experiments

The primary philosophy underlying behaviorism is that only data gathered through scientific observation can yield reliable results. It is the many fascinating experiments resulting from this philosophy that truly made the behaviorists famous.

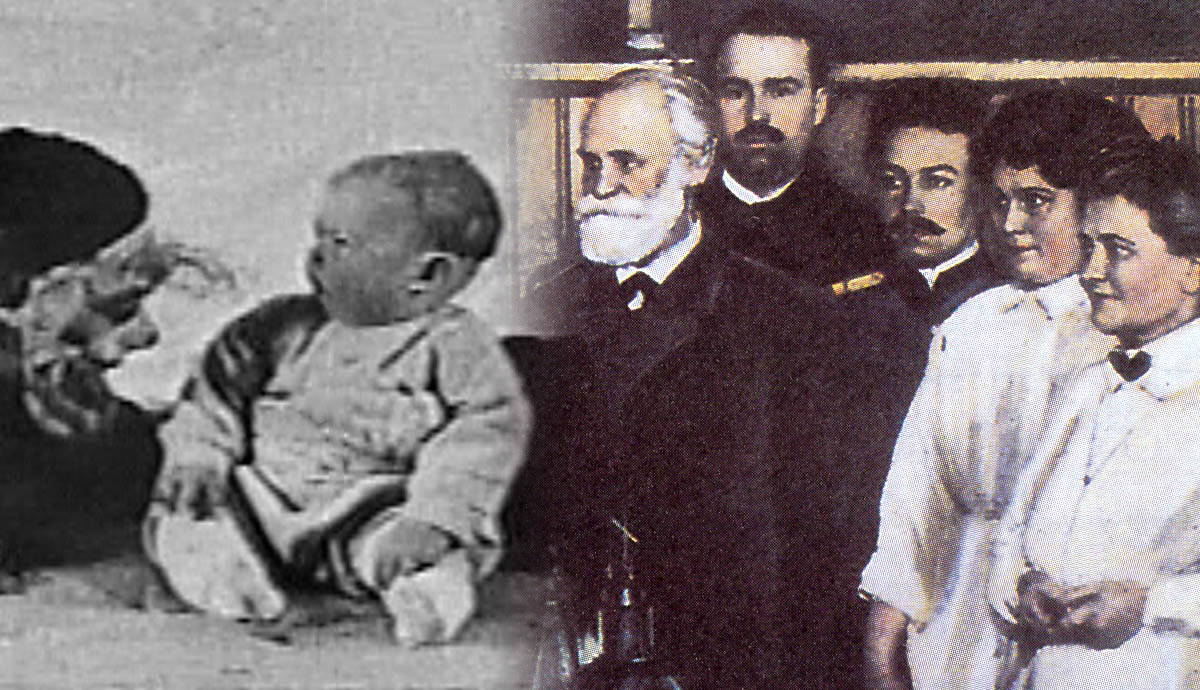

1. Pavlov’s dogs – 1898-1925

The true genesis of behaviorism as a theory came in the 1890s when physiologist Ivan Pavlov was studying the digestive systems of dogs. He set up a system to measure the amount of saliva produced by dogs during feeding, but noted that this began as soon as the dogs heard the footsteps of the assistant who fed them.

He went on to discover that any phenomena that the dogs learned to associate with food elicited the same response. This revealed itself to Pavlov as an important scientific discovery, and he spent much of his remaining career devoted to it’s study.

In his 1902 work, The work of the digestive glands, Pavlov noted that an unconditioned stimulus (food) involuntarily brought up an unconditioned response (salivation). He then found a neutral stimulus, or something that did not initially elicit a response from the dogs, in this case the ticking sound of a metronome. He began switching on the metronome before and during feeding time, and found that after a few repetitions the metronome alone was enough to elicit a salivation response.

2. The Little Albert Study – 1919

In the earliest experiment in classical conditioning applied to humans, Watson & Rayner set out in 1920 to explore whether a persistent fear response, or phobia, could be created. What followed was an experiment that would not meet modern ethical standards.

Albert B. was 9-months-old when Watson and Rayner first introduced him to a series of harmless objects; a white rat, a monkey, a rabbit, masks, smouldering paper and the sound of a four-foot pipe being struck by a hammer. They observed that he showed no fear to any of the objects but became scared and cried when the pipe was struck.

Seven times over the following weeks, Albert was exposed to the rat at the same time the pipe was struck. He cried each time, and also began crying at the sight of the rat alone. This was the conditioned response Watson and Rayner had been hoping to elicit. They found that Albert responded the same way upon seeing other small animals or white, furry objects: stuffed animals, a Santa Claus beard and Rayner’s fur coat.

The researchers continued testing Albert a month after the conditioning had ended and found that he continued displaying the conditioned behavior.

3. Thorndike’s Cats – 1898-1905

Thorndike would place a hungry cat into a box that opened when the cat stepped onto an internally-mounted switch. Outside the box he would place a bowl of food to motivate it to escape.

He noticed that the cats he tested would meow and roam around the inside of the box looking for a way out, until accidentally stepping on the switch would reward them with access to the food. When the same cat was tested multiple times, the time taken for the cat to open the box generally decreased with each repetition. He further found that the rate of decrease went up each time, before plateauing once the cat had learned to perform the task efficiently. This led to him coining the term, ‘learning curve’.

Thorndike contended that the increased performance of the cats did not indicate an understanding of the mechanics of their predicament; “There is no reasoning, no process of inference or comparison; there is no thinking about things, no putting two and two together; there are no ideas – the animal does not think of the box or of the food or of the act he is to perform.”

4. The Skinner Box

Burrhus Skinner pioneered the method of placing animals inside a small box to subject them to operant conditioning. These were constructed to block outside stimulus and keep the animal contained while they were trained to perform certain behaviors.

They were used in experiments similar to Thorndike’s, as well as in classical conditioning studies. In these, animals were taught to associate an action, such as turning to the right, with a light bulb going on and a reward of food. Eventually, the animal could be made to turn to the right simply by switching on the light bulb and no reward.

In other experiments, the animals were conditioned to press a lever, either to attain a reward or to stop electric shocks. Like Thorndike, Skinner found that the animals completed these tasks in progressively shorter times.

The Lessons and Legacy of Behaviorism

As the scientific world view grew, it gradually cast many of the previously-authoritative institutions of man into a crisis of legitimacy. As the technological triumphs of the scientific world-view piled up, skepticism grew for insights and perspectives that did not meet these new standards.

The behaviorists attempted to address this by reconciling psychology with the scientific method of observation and enquiry. This also had implications for the field of philosophy; E. O. Wilson (1975) suggested that ‘ethical philosophers intuit the deontological canons of morality‘ by consulting their own ’emotive centers’. He further suggested that ‘ethical behaviorism’ could provide a means of ‘interpreting the activity of the emotive centers as a biological adaptation’. Thus, moral commitment could be interpreted as a set of behaviors learned by children through operant conditioning (Wilson, 1995).

Critics argue that modern cognitive psychology has rendered behaviorism an obsolete discipline (Harzem, 2006). Blanchard (1965) claimed that the rejection of internal processes by behaviorists was detrimental to the development of psychology itself; ‘some headaches appear to be produced by anxiety and fear, others by an allergy to chocolate. […] To the extent, then, to which psychology can talk in terms of physical causation, it gains precision, objectivity and control.’

The behaviorists established many of the most profound psychological truths that are taken for granted today; insights into the mechanisms behind the training of animals, the learning of children and the manner in which societal norms are inherited. They attempted to identify and address what they saw as the weaknesses of the previous dominant methods, much as cognitive psychologists did after them. As Isaac Newton (Merton, 1985) wrote in a letter to fellow scientist Robert Hook;

“If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

Bibliography

Blanshard, B. (1965). Critical Reflections on Behaviorism. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 109(1), 22-28. Retrieved September 4, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/985775

Hobbes, T., & Missner, M. (2016). Thomas Hobbes: Leviathan (Longman Library of Primary Sources in Philosophy). Routledge.

Hobbes, T. (1999). The elements of law, natural and politic: Part I, human nature, part II, de corpore politico; with three lives. Oxford University Press, USA.

Merton, R. K. (1985). On the shoulders of giants: A Shandean postscript (Vol. 63). Harcourt.

Thorndike, E. L. (1927). The Law of Effect. The American Journal of Psychology, 39, 212-222.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1415413

Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychological Review, 20(2), 158–177.

Wilson, E. O. (1975). Some central problems of sociobiology. Social Science Information, 14(6), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847501400601

Wilson, E. O. (1995). The morality of the gene. Issues in evolutionary ethics, 153-164.