War has been a commonplace event occurring over centuries. War and medicine as separate spheres are deeply ingrained in society, and combined, they form an alliance that can be viewed as destructive or beneficial. Both also rely on the progression of modernity. As technological, social, and scientific advancement progresses, war can be seen as a trigger for medical advancement due to the rapid need for cures of new wounds and epidemic diseases. However, an ongoing debate continues between historians regarding whether war is advantageous or detrimental for the expansion of medical knowledge. This article will explore how the introduction of modern warfare contributed to modern medical advancements.

Medical Advancements at the Beginning of Total War

In 1914, the first total war of the century was just beginning; an environment where ignoring all moral or ethical concerns was key to disable the enemy. There was no limit on the type of weapons used, and biological, chemical, nuclear, and other weapons were all still waiting to be discovered. World War I saw over 30 nations declare war, using all available resources and prioritizing warfare over non-combatant needs. The physical scale in both spread and manpower combined with the emergence of new weapons set the precedent that this conflict would necessitate “rapid developments in all areas of medicine and medical technology.”

This change in warfare is evident in many paintings that arose due to World War I, most notably, The War (Der Krieg) by Otto Dix. The painting, consisting of four panels, captures the devastation of WWI. It represents death and decay awaiting the soldiers. This work aims to show the brutality and insanity of the war through shockingly realistic depictions of the wounded and dead soldiers.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly NewsletterThis challenge was first witnessed in the layout of the battleground. With most of the fighting set in the trenches of Europe and with the unexpected length of the war, soldiers were often malnourished, exposed to all weather conditions, sleep-deprived, and often knee-deep in the mud along with the bodies of men and animals. In the wake of the mass slaughter, it became clear that the “only way to cope with the sheer numbers of casualties was to have an efficient administrative system that identified and prioritized injuries as they arrived.” This was the birth of the Triage System.

The system operated by separating all wounded soldiers into three groups “that could be summed up as ‘trivial, treatable and terrible.’” Those with minor wounds were treated first and sent back to the front lines. The next priority was those who required severe but treatable wounds. Finally, were those who were given a low chance of survival. Without the rapidity of the war, the triage system may have been discovered too late if at all. However, due to its discovery, it “brought organization and efficiency to urgent medical care, and after the First World War, it became standard practice in military medicine.”

One condition of the trenches that benefited from the triage system was immersion foot syndrome, commonly known as trench foot. Trench foot was a direct consequence of trench construction. Dug-in land near or at sea level left the men standing, eating, and sleeping in puddles of water. The symptoms included swelling, numbness, and discoloration of the feet. By the end of the war, a total of 74,000 Allied troops are believed to have suffered from the condition.

Medical personnel were now faced with creating an effective treatment as an alternative to amputation, commonly practiced in war. The remedy was simple: cleaning and drying feet as often as possible, followed up with a change of socks. Other methods involved rubbing ”whale oil into their feet, and even a ‘stamping drill’ of stomping and rubbing their feet in unison to get the blood flow going. Soldiers also tried digging drainage ditches and laying duckboards through communication trenches to avoid flooding.”

However, the triage system was only successful in this instance “if patients were dealt with quickly and constantly reassessed while waiting for treatment, because a ‘treatable’ case might become a ‘terrible’ case if the patient had to wait too long for attention.” If left untreated, severe cases would also result in amputations to reduce the spread of infection.

The sanitary conditions of the trenches meant that untreated wounds, although not life-threatening at the time, would lead to death as bacteria entered. Ceri Gage, Curator of Collections at the Army Medical Services Museum, is very clear on the impact of bacteria in warfare, stating that “a simple cut to a finger from cleaning your gun or digging a trench could quite quickly become infected and develop into pneumonia.”

Injured men would be transported by cattle car to the nearest city. No bandages, comfort, food, nor water were provided. The attitude towards amputations and the desperate need for change is evident in the diary of George Crile, a volunteer physician. Crile wrote, “In the early stages of the war, especially within six weeks, 300,000 French soldiers were wounded…more than 20,000 amputations had been made.” However, as stated by the father of medicine, Hippocrates, “war is the only proper school for a surgeon,” and World War I was pivotal in the advancement of wound treatments.

The change started with the introduction of French physician Alexis Carrel who, upon enlisting in the French Army, was shocked at the use of amputations as a first and only result for wounds infected with bacteria. Together with Henry Dakin, they created the “Carrel-Dakin” method, which involved opening the wounds to thoroughly irrigate them with Sodium Hypochlorite solution. This was instilled by means of small rubber tubes closed at the end and perforated with 6-8 holes at half-inch intervals. While the method may have come about in time, the war necessitated rapid developments in medicine and medical practice; it allowed doctors to work on a large scale of patients all suffering from the same disease

WWI Medical Advancements: The Thomas Splint

Similar advancements came in the form of the Thomas Splint. Introduced in 1865, the splint gained momentous popularity in the first world war when the inventor Hugh Owen Thomas’ nephew became a major general inspector for orthopedics in the military. New weapons saw shrapnel destroy soldiers’ skin, leaving behind wounds that had never before been witnessed. As a result, new surgical techniques were vital. The success of the Thomas Splint can be seen in mortality numbers: in 1914, 80% of soldiers inflicted with broken thigh bones died. The use of the Thomas splint resulted in an 80% survival rate by 1916. The splint allowed medical personnel to move a patient without causing more damage and even reduced the pain. The success of the Thomas splint can be seen in its continued use in World War II as well as in the present day.

Blood Transfusions: A Pivotal Moment in Medical Advancements

The original process of blood transfusions relied on both the donor and patient lying next to each other, with both blood vessels exposed, connected by rubber tubing. This led to many complications such as clotting, patient self-restraint, and inability to measure how much blood was passing between the two individuals. As a result, blood transfusions became a pivotal medical advancement that occurred due to the First World War.

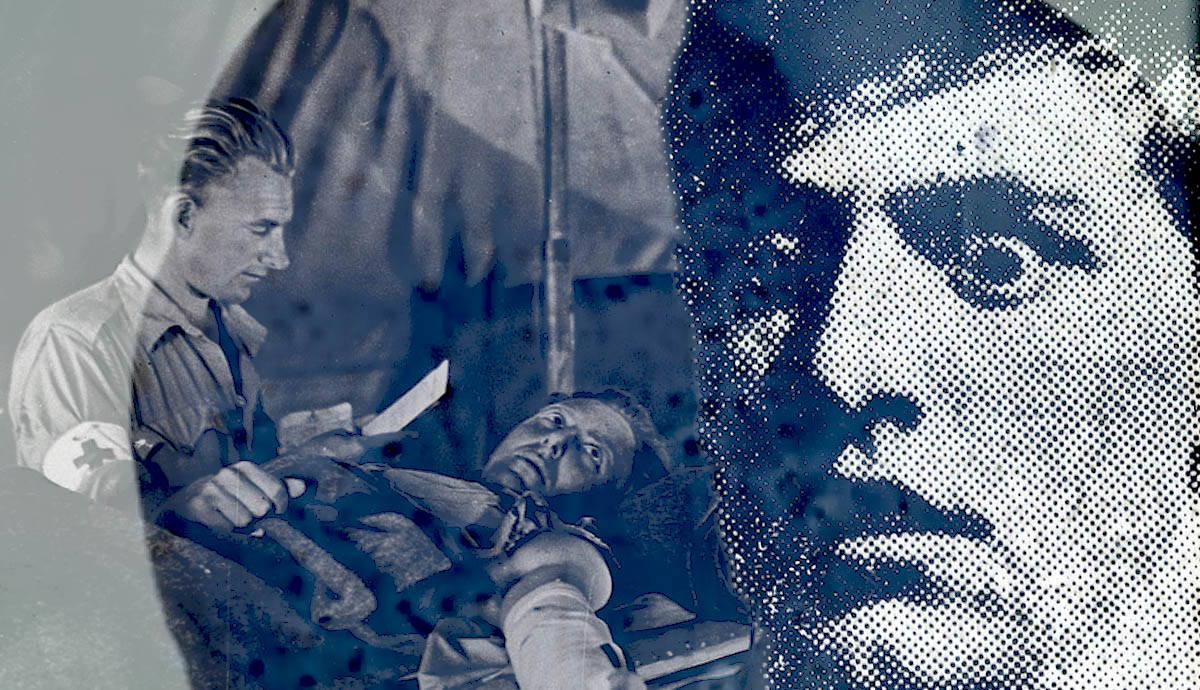

While it was not an innovation of war, the process of blood transfusion was greatly refined during World War I and ultimately contributed to medical progress. Previously, all blood stored near the front lines was at risk of clotting. Anticoagulant methods were implemented, such as adding citrate or using paraffin inside the storage vessel. This resulted in blood being successfully stored for an average of 26 days, simplifying transportation. The storage and maintenance of blood meant that by 1918 blood transfusions were being used in front-line casualty clearing stations (CCS). Clearing stations were medical facilities that were positioned just out of enemy fire.

In the book Shell Shock, Wendy Holden praises this advancement by stating, “making these distinctions was a major breakthrough…the new system meant that mild cases could be rested then returned to their posts without being sent home” (Wendy Holden, 1998). This, combined with the stored blood, increased a soldier’s chances of survival from many wounds, infections, shock, and hemorrhaging. Additionally “transfusions could also aid with carbon monoxide poisoning and wound infection, and so were increasingly used during and after operations as well as before.”

The USA And Its Involvement In Blood Transfusions

The US Army’s intervention into the war proved the most pivotal in advancing the process of blood transfusions. It delivered more physicians to the front lines with broader knowledge, such as Oswald Hope Robertson. When sent to the front lines, Robertson developed plans for what would become the first blood bank. He used citrated blood and transportation means via ammunition boxes packed with sawdust and ice, meaning that blood could be transported faster and stored for longer periods. These processes were adopted throughout the war as soldiers were issued standardized transfusion kits, allowing the procedure to occur before reaching a casualty clearing station.

These methods developed by Robertson were fundamental in medical advancement surrounding blood transfusions. Its successes can be measured in that by the end of the war, Robertson was training other medics in his techniques. Consequently, the First World War “introduced transfusion methods to more doctors and in more standardized procedures than might have occurred in peacetime, and convinced them of its benefits.” After the war, these results and practices were promoted to a new status in civilian medical practice.

World War I and Mental Illness

One of the most profound medical advancements resulting from World War I was the exploration of mental illness and trauma. Originally, any individual showing symptoms of neurosis was immediately sent to an asylum and consequently forgotten. As World War I made its debut, it brought forward a new type of warfare that no one was prepared for in its technological, military, and biological advances.

Conscription led to rising difficulties in producing mentally capable men. Due to the duration and mortality rate, more men were needed on the front lines and therefore conscripted in bulk. Accordingly, “many who might otherwise have been identified as mentally defective were simply absorbed into the anonymous mass of fighting men” (Cooter, Harrison, Sturdy, 1998).

With the introduction of new weapons, a new psychiatric disorder came to light known as Shell Shock. This idea was first recognized as Railway spine injury in the late 19th century, a direct result of forceful impact resulting in psychological disorders. Shell Shock was a direct result of the conditions of war: close-range bombings, lack of sleep, malnutrition, and emotional distress from witnessing mass death, and as a result “for some people, the physical and mental damage caused by war lasts a lifetime.” The severity of this situation was primarily overlooked by the collective thought that the soldiers were malingering. During World War I, “309 British soldiers were executed, many of whom are now believed to have had mental health conditions at the time.” The need for medical advancement had never been greater as mental illness was taking curable lives.

However, it must also be noted that many soldiers did not have to be on the front lines to experience psychological trauma as a result of World War I. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner is a prime example of this. Although he never actually fought in the war, he did see some of the atrocities of World War I and incorporated them into his works. His trauma is especially depicted in his post-war art: dressed in a soldier’s uniform with a vacant expression, his Self-Portrait as a Soldier (1915) can be used to demonstrate the necessity for medical advancement in World War I as it spanned all areas of society.

Coined in 1915 by Charles Myers, Shell Shock was a direct catalyst for medical advancement in war as it provided hundreds of test subjects in which these symptoms could be seen. This breakdown in mental health ultimately led to an insurgence of psychiatrists being conscripted into the armed forces. With government backing, they “gradually began to infiltrate Army recruitment, training and morale” (Holden, Shell Shock, 1998). They were subjected to tests during training to prepare them both mentally and physically for war conditions, such as gradual exposure to controlled explosions. Additionally, as a result of World War I, “for those who were discharged or returned after the war, some treatments were available.” Hypnosis, electro-shock therapy, and many other practices learned from the conflict were carried in the post-war era and shaped psychiatric care as we know it today.

A Long-Awaited Advancement: Base Hospitals and Casualty Clearing Stations

Another successful innovation came in the form of the base hospitals and clearing stations. These allowed doctors and medics to categorize men as serious or mild, and results came to light that many stress-related disorders were a result of exhaustion or deep trauma. “Making these distinctions was a breakthrough…the new system meant that mild cases could be rested then returned to their posts without being sent home.”

War also caused Freudian ideas to be taken much more seriously, particularly his belief of neurasthenia, which “could be cured by making a patient confront his experiences and recall painful memories under hypnosis…later to become vital tools in the battle for the minds of the First World War participants” (Holden, 1998). This breakthrough in medical progress thereby proves that war led to a positive headway in medicine. By the influx of a greater range of diseases, both mental and physical, ideas that were criticized in the past came to have more meaning in times of war.

This, therefore, marks a clear advancement in medicine as a result of the First World War as it not only improved military efficiency but also provided those with genuine mental health problems with an effective treatment that would continue in the post-war era.

Chemical Warfare: Its Introduction In World War I and the Following Medical Achievements

Similar to Shell Shock, other medical advancements were made due to the increasing number of new modes of warfare. An example of this presented itself in 1915 in Ypres, France, where German soldiers released canisters of chlorine gas. Widespread confusion and terror spread as men with prolonged exposure began to die with no physical wounds. The use of cylinders required heavy reliance on the weather, specifically the direction of the wind, which could turn an attack into self-sabotage.

The introduction of chemical warfare in the First World War introduced several different gas weapons such as mustard gas, bromine, and phosgene, which in turn would gain larger traction in the wars to come. Referred to as the “Chemists’ War” due to the mobilization of scientific, medical, and military spheres, public health practitioners could defer that the threat of chemical warfare was not confined to the front lines but also against civilian populations.

However, as devastating as the scenes were, it allowed “modern military medicine to develop sadly at the price of many lives.” This protected not only soldiers but civilians whose occupation involved contact with gasses. While treatment was difficult to discern, habituation and adoption of coping strategies were continuously evolving. A prime example of this was the invention of the gas mask. Gas masks would undergo redesigning many times as the list of chemicals used in warfare grew, with the first model being a piece of cloth that covered both the mouth and nose (not unlike the masks we see today), with a cotton pad laced with thiosulfate to neutralize the chlorine gas. “The First World War triggered a medical renaissance” with the invention of many medical advancements and retheorized practices, such as the gas mask. This can be seen in the continuous use of gas masks in the Second World War.

This primitive model soon led to the introduction of the small box respirator, which was introduced to soldiers in 1916. It consisted of a rubberized mask to cover the face and head that joined to a rubber hose, connected to a canister made of tinplate containing a chemical absorbent. It provided defense against a majority of the new chemicals witnessed on the front lines.

However, where medicine advances, so must weapons. It did not take long for the German army to deploy the “King of Battle Gases.” Introduced in 1917, Mustard gas differed from the norm in that it was a vesicant that would result in large blisters when it encountered the skin. The evolution of chemical gases in the First World War necessitated a fast solution from medical professionals on the front lines as the care of the victim required extra steps. While the baseline of rest and oxygen was kept in place for all chemical gas victims, mustard gas victims also required a hot bath to remove any traces of the gas which clung to skin and clothing. Their uniforms were also decontaminated, and eye baths became common practice. World War I enabled the newfound medical practices to be sent back to civilian society, which would have otherwise been undiscovered.

In conclusion, it can be seen that World War I had a significant impact on the advancements of medicine. Arguably, several advancements would have taken place regardless; however, without the war, the timeline of these medical advancements would have been considerably slower. The conflict gave doctors and physicians an unprecedented number of patients and test subjects on which to trial and perfect treatments, as well as exposed much of the world to different forms of warfare. Based on the examples outlined above, we can see many “medical techniques used today have their origins in those developed during World War One.”