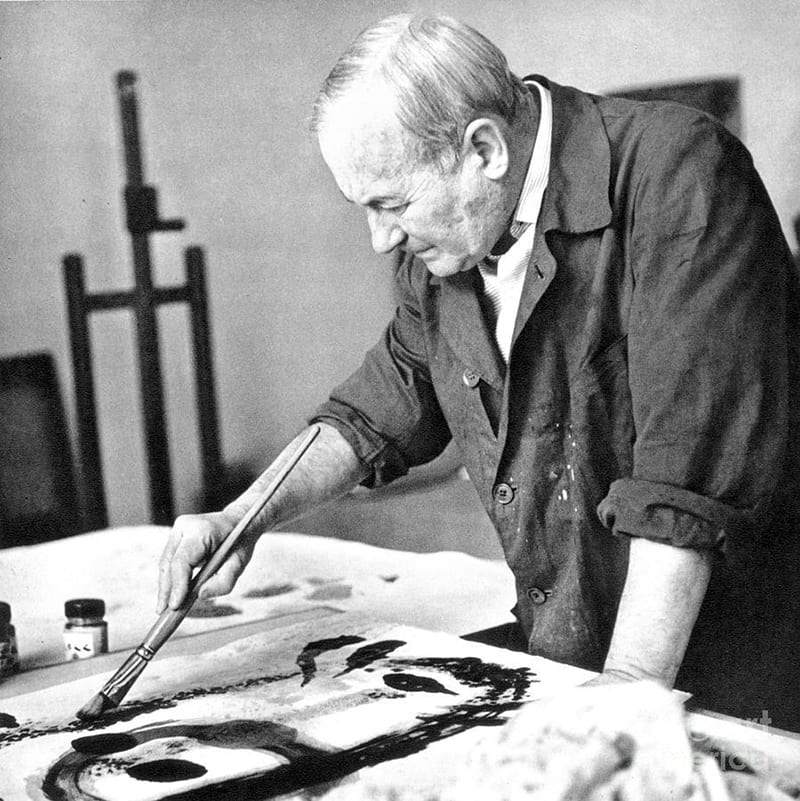

Joan Miro was a leading light in early 20th century art, developing a highly distinctive, instantly recognisable style that is more popular today than ever. Influenced as much by Catalonian folk art as the French Surrealists. His vibrant, vitally expressive language speaks of a universal desire for individuality and freedom, particularly during the troubled war-time years of his prime. Recognised today as a potent precursor to American Abstract Expressionism, his unparalleled voice remains one of the most powerful ever to emerge in the history of art.

Early Years

Joan Miro was born in 1893 in Barcelona to a family of craftsmen; his father was a watchmaker and goldsmith, while his grandfather was a cabinetmaker. Though he demonstrated an early aptitude for drawing, Miro’s parents pushed him towards a more sensible career choice, encouraging him to study at the School of Commerce before taking on an office job as a clerk.

He remained there for two years, but left after having a nervous breakdown, followed by a severe bout of typhoid fever. Miro’s family bought a farm in the countryside of Montroig outside Barcelona as a place of refuge for Miro, and it was here that he was able to find his true calling as an artist.

Painting and Poetry

Miro began studying art in Barcelona in 1912, where he discovered the work of various avant-garde artists and Catalan poets, writing, “I make no distinction between painting and poetry.” As a student he experimented with various techniques, including drawing “by touch” rather than sight.

His early paintings spanned various subjects including still-life, portraiture and landscape, characterised by vivid colours and expressive mark-making, which revealed the influences of Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cezanne and the French Fauvist painters, combined with a love of the naïve, vibrant language of Catalan folk art.

The Influence of Paris

Following graduation, Miro struggled to find recognition for his art in Barcelona. Instead, in 1920, he headed to Paris, meeting various Surrealist artists including Pablo Picasso, Andre Masson and Tristan Tzara, who had a profound impact on his practice.

Following his return to Montroig, Miro described how he “immediately burst into painting, the way children burst into tears.” In the years that followed Miro moved between Paris and Catalonia, spending Summers in Spain and winters in Paris. But he was desperately poor and described how he sometimes “saw shapes on the ceiling” following bouts of extreme hunger, which would make their way into his paintings.

Finding Success

In Paris, Miro became associated with the Surrealist group, often taking part in their organised group shows, although he refused to sign their manifestos, preferring to remain slightly apart. Even so, the imagery in his art reflected the “pure psychic automatism” of Surrealist thought, with child-like, biomorphic forms suggesting dreamy, unconscious states of mind. His paintings grew increasingly abstract over time, featuring brightly coloured, geometric shapes and simple linear designs over hazy, painterly backgrounds.

After marrying Pilar Juncosa in 1929 and having a child, his art grew ever more popular, selling in France and the United States, while he branched out into a wider range of media, including printmaking, sculpture and collage.

Everything is Lost

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly NewsletterThe success of Miro’s career was brought to an abrupt end by the global depression and in 1932 he moved with his family back to Barcelona. A period of dramatic political instability followed – the Spanish civil war broke out in 1936, followed by the outbreak of the Second World War. Miro and his family eventually made their way to Mallorca, although he was deeply unhappy, commenting, “I was very pessimistic. I felt that everything was lost.” In response, he made small, dark works on paper, titled Constellations, 1939-41, capturing the star filled night sky as a symbol of his desire for open space and freedom from war.

Later Years

The Museum of Modern Art in New York hosted a major retrospective of Miro’s work in 1941, and following the end of the war, Miro’s popularity and influence spread across the United States, leading to his huge mural commission in Cincinnati in 1947.

Returning to live between France and Spain, Miro branched out into new media in the 1950s and 60s including printmaking and sculpture, while a series of retrospectives, awards and honours celebrated the depth and breadth of his legacy. By the time of his death in 1983, Miro’s place in art history as an international, Modernist master was already set.

Most Expensive Art

Did you Know?

Miro’s first solo exhibition at the Dalmau Gallery in Barcelona was ridiculed by critics and the public, while some visitors even vandalised his artworks, prompting Miro to leave Spain for Paris.

Given this early bad reception, Miro developed a dislike for art critics, describing them as “more concerned with being philosophers than anything else. They form a preconceived opinion, then look at the work of art. Painting merely serves as a cloak for their emaciated philosophical systems.”

Writer Ernest Hemingway was a huge fan of Miro’s paintings and bought one of Miro’s artworks, La Masia, 1921-22, as a gift for his wife. Both Hemingway and his friend were keen on the same painting, depicting a farm in Catalonia, so they rolled a dice to see who would get it.

methods for making art, including finger painting, rubbing with his fists, and even stamping on the canvas with his bare feet – footprints are just visible in his painting Toile Brulee, 1973.

Miro and his Surrealist contemporaries were greatly influenced by the psychoanalysis of Sigmund Freud and attempted to induce altered states of mind to find subject matter for their paintings, including experimenting with “hallucinations of hunger.”

Miro only just escaped German forces in France during the outbreak of World War II. Living in Varengeville, he and his family caught the last train to Paris, and found space on the final train out of Paris into Spain.

In relation to his fantastically Surreal later paintings, which feature biomorphic, ambiguous forms, art historians defined the term “miromorphosis.”

Miro designed a tapestry for the World Trade Centre in New York in collaboration with Josep Royo, titled the World Trade Centre Tapestry. Sadly, the tapestry was one of many artworks to be destroyed in the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

The Fundacio Joan Miro, in the Parc de Montjuic in Barcelona, was founded in 1975 and houses a vast array of Miro’s artworks, including 217 paintings, 178 sculptures, 9 textiles and over 8,000 drawings.

Miro was astonishingly prolific and left behind a staggering body of work, including around 2,000 paintings, 500 sculptures, 400 ceramics, 5,000 drawings and over 1,000 prints, which exist in public and private art collections all around the world. He also made ceramics, murals and tapestries, and even designed costumes and props for the ballet, working well into his later years.