Kublai Khan completed the decades-long Mongolian conquest of China in 1279, becoming the first ruler of the Yuan dynasty. Despite a fierce protracted conflict not well-suited for the Mongolian way of war, Kublai Khan still managed to absorb the Song dynasty into his empire, marking the first time in history that the whole of China was conquered and ruled by a foreigner. Perhaps most ironically, the Mongol Empire’s defeat of China was assisted by its acceptance of ideas put forth by China’s most famous military strategist, Sun Tzu.

The Mongol Empire’s China Problem

The Mongol Empire was established in 1206 by the infamous Genghis Khan in the Steppe of Central Asia. At the height of its power, it constituted the largest contiguous land empire in history, covering over 9 million square miles. The conquest of China was the Mongol Empire’s most challenging campaign, spanning decades and several khans. Southern China proved unsuitable for the Mongols’ traditional cavalry warfare because of the prevalence of its mountains and rice fields. To make things more challenging, the Chinese were adept at siege defense and had the advantage of gunpowder.

Put almost entirely on the defensive, China focused on surviving a protracted war in mountain strongholds supported by agricultural areas and adjacent rivers. This also maximized the impact of China’s infantry, which would be at a severe disadvantage against Mongolian cavalry in open battle. Additionally fortuitous, these strongholds were close enough geographically to avoid the danger of being isolated and annihilated one by one. China further divided its infantry into small units suited to guerilla warfare and stationed its navy in rivers to defend its fortresses.

In China, Kublai Khan’s forces faced challenges that directly countered their preferred style of warfare. The terrain was unforgiving to cavalry and forced the army to take circuitous routes. Chinese strongholds were heavily defended and supported by the navy. Not only did the Mongols not have a naval force to match, but the Chinese fleet could further limit Mongol movement and even outflank their cavalry at times. Let’s take a look at the Mongol way of war and how it aligned with Sun Tzu‘s teachings as a prerequisite for how the Mongols overcame the China problem.

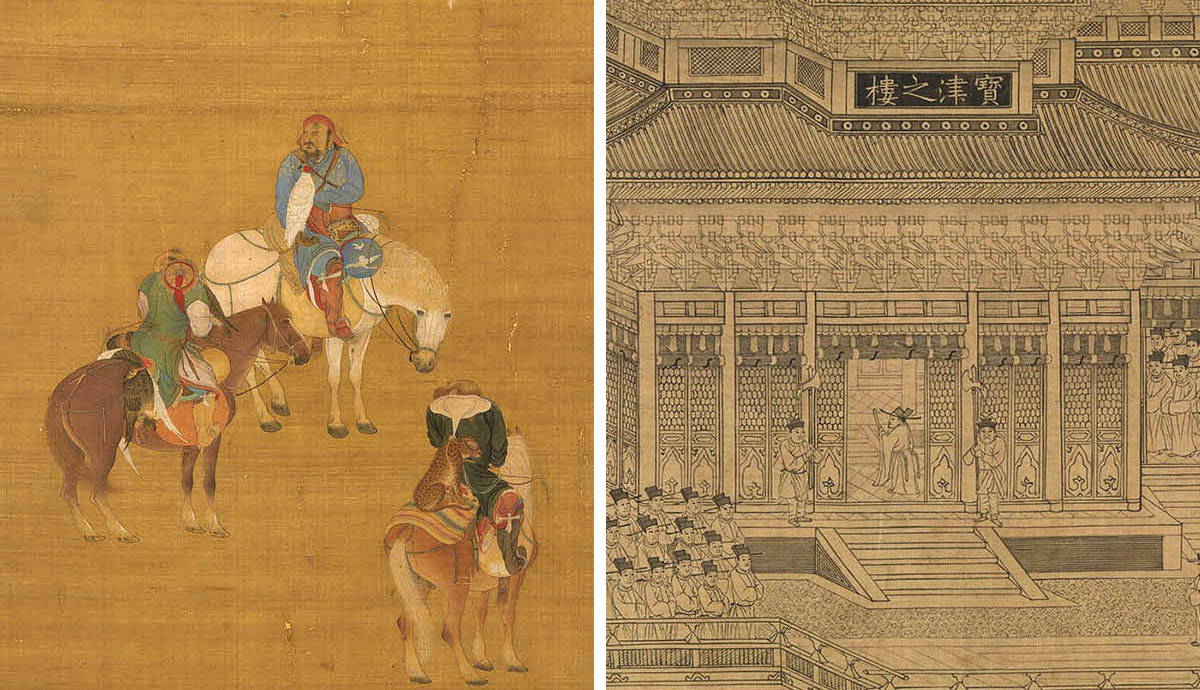

The Nomad: Mounted Archers

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

Due to their nomadic lifestyle, Mongol warriors were traditionally elite horsemen and deadly archers, learning how to ride a horse and shoot a bow as toddlers. As part of the army, they engaged in archery training and various unit drills to solidify their maneuverability and discipline as a group. They preferred projectile weapons to hand-to-hand combat. The average Mongol archer could easily outshoot his opponent with his long-range composite bow, which had an accurate range of 300m. To demonstrate the advantage this bow offered, the crossbow used by Western European armies at the time had an accurate range of only 75m, while the famous English longbow of several centuries later reached 220m. To supplement their bows, Mongol warriors also carried lances, spears, or swords for close combat, and often wore light lamellar armor.

The cavalry often adopted maneuvers similar to that of the mass hunt. Horsemen would fan out and form a ring several miles across, then slowly contract until all targets are trapped inside with no escape. The discipline, coordination, and communication required for this hunting maneuver easily translated to the battlefield, making for a highly disciplined and devastatingly mobile force. While cavalry was very much traditional to the Mongolian fighting style, it also happened to couple well with Sun Tzu’s emphasis on swift and decisive movement. This hunting maneuver exemplifies and indicates the depth to which the Mongols understood the crucial importance of mobility.

Despite the looser rigidity of its nomadic army, the Mongol Empire nevertheless infused the crucial element of discipline to ensure that warriors would adhere with absolute obedience to their commanders and work as a unit rather than as individuals. As can be imagined, Mongol cavalry worked best on open ground reminiscent of their homeland and was very difficult to defeat under such conditions. However, China’s mountainous terrain proved the first major obstacle to the Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty.

Espionage and Illusory Tactics

Another tactic frequently used by the Mongols to shattering effect was that of espionage. Here, many similarities can be seen between the Mongol practice and Sun Tzu’s teachings, especially that of deception and knowing one’s enemy. For example, each Mongol campaign began by gathering intelligence on the enemy from merchants, spies, scouts, or expeditionary reports. Understanding the importance of up-to-date information, imperial messengers were allowed to requisition horses to get news back to the Khan in mere days from anywhere in the empire. Armed with this intelligence, the Mongol Empire planned its detailed campaign strategy before even departing.

As for deception, Mongol tactics included a wide range of surprise attacks and ambushes. Thanks to the mobility granted by their horses, Mongol mounted archers were masters at hit-and-run, flanking, and envelopment maneuvers. They often feigned retreat to coax the enemy into chasing them before wheeling around and obliterating them. They frequently encircled and broke the enemy’s strength with an arrow storm before moving in for the definitive kill. Because of this emphasis on subterfuge, mobility, and projectile weapons, the Mongol Empire didn’t need superior numbers to cripple the enemy on the battlefield. As explained by Sun Tzu, deception is a superb way to upset asymmetrical balances of power while also minimizing one’s losses.

Sometimes, the Mongols even avoided combat altogether in search of a more ideal battlefield. While doing so, they divided their forces into disparate targets until opportunity allowed for a quick regroup and surprise attack. These Fabian tactics are particularly useful in wearing down a defensive enemy before even engaging in battle. And once again, it is decidedly reminiscent of Sun Tzu’s mandate to only engage in battle when one holds a clear advantage.

Well aware of psychological warfare, the Mongol Empire is infamous for regularly massacring conquered towns to discourage further resistance. It also widely used propaganda to exaggerate the size of its forces. When the Mongols invaded Szechuan in 1258, the khan spread rumors that his 40,000 force actually numbered 100,000. They regularly used subterfuge to confuse the enemy and were quick to take advantage of any internal dissension among enemy ranks.

The Mongol Army

With its cavalry and careful planning, the Mongol Empire created a vast empire. But as the Mongol Empire expanded and evolved, so did its military character. Genghis Khan first began the process of military transformation by consolidating the loose Mongolian confederation into an army. He organized his forces along decimal lines of ten, 100, 1,000, and 10,000 and made a soldier’s military unit his new social “tribe.” The army was deployed in three flexible corps: right flank, center, and left flank. After conquering a territory, the Mongol Empire left a tamma military force to secure the area and expand Mongolian influence.

Kublai Khan’s diverse forces required considerably more organization than Genghis Khan’s light cavalry troops half a century before. Men from conquered peoples were absorbed as infantry to support the Mongolian cavalry and as engineers to bolster the Empire’s ability to conduct sieges and construct roads to ease its logistics. The Mongol Empire integrated the different skill sets possessed by various peoples, allowing each to fight in their traditional way. Due to this practice, the army expanded to include heavy cavalry, shock troops, regular infantry, engineer corps, and other forms of non-nomadic forces. Fortunately for his China problem, this practice also gave Kublai Khan the keys to success in a campaign most unsuitable to the Mongols’ traditional way of nomadic warfare.

Kublai Khan and the Leadership’s Winning Strategy

While the Mongol Empire is famous for its nomadic cavalry, its strategic capacity should not be underemphasized. Its army was highly developed, disciplined, and wielded its traditional structures alongside adopted ways of war to overwhelming effect. Far from being a disorganized mob of marauders, the Mongol Empire intelligently planned and organized each campaign and maintained the strict balance between obedient yet autonomous generals.

Mongolian strategy typically unfolded as follows: After gathering intelligence and organizing its troops, the Mongol Empire declared war, often giving the enemy an ultimatum and options for surrender. It determined its campaign strategy in a war council and thereafter expected its commanders to adhere to the timetable agreed upon. As long as they coordinated according to the timetable, commanders were allowed a high degree of independence. Due to their cavalry, Mongol strategy clearly had a central component of maintaining and utilizing mobility. As such, they often adopted a three-pronged invasion. This gave good opportunities for destroying the enemy’s army and smaller fortresses, saving the larger strongholds for last. Once the field army was destroyed, the Mongols could besiege cities at their leisure. Throughout, the Mongols targeted enemy leaders. Killing leaders not only left troops in disarray but also eliminated the possibility of the enemy easily regrouping.

But since cavalry was ineffective in the terrain of southern China, how did the Mongol Empire defeat the Song dynasty? Kublai Khan simply but brilliantly circumvented his army’s shortfalls by relying on those more familiar with Chinese warfare. Namely, Chinese deserters and Korean fighters. This shifted the army’s structure to promote infantry commanders in the Song campaign. Additionally, Kublai Khan incorporated a number of innovative technologies to combat Chinese strongholds. Firstly, “thunder crash bombs” were launched over the walls with traction trebuchets. At the siege of Xiangyang in 1273, the counterweight trebuchet proved effective enough to crush city walls. Secondly, the Mongols built a navy to be commanded by Chinese and Korean officials. With this fleet, the Mongols outmaneuvered and blockaded the Chinese navy. With these two adaptations alone, the Mongols neutralized China’s main advantages.

The Irony of Sun Tzu in the Mongol Empire’s Success

The war lasted decades because of the fierce Chinese defense. However, in the end, the Mongol Empire prevailed. Throughout this bitter, protracted war, the Mongols demonstrated multiple examples of Sun Tzu’s teachings in action. In addition to the espionage and deception already expounded upon, their sheer flexibility and willingness to adapt were, at the core, completely in line with Sun Tzu. As he writes, “Just as water retains no constant shape, so in warfare, there are no constant conditions. He who can modify his tactics in relation to his opponent, and thereby succeed in winning, may be called a heaven-born captain.” The Mongols’ willingness to adopt new techniques and tactics as circumstances required them, made their way of warfare that much more powerful. In the end, it was the key to Kublai Khan’s success in conquering the whole of China.