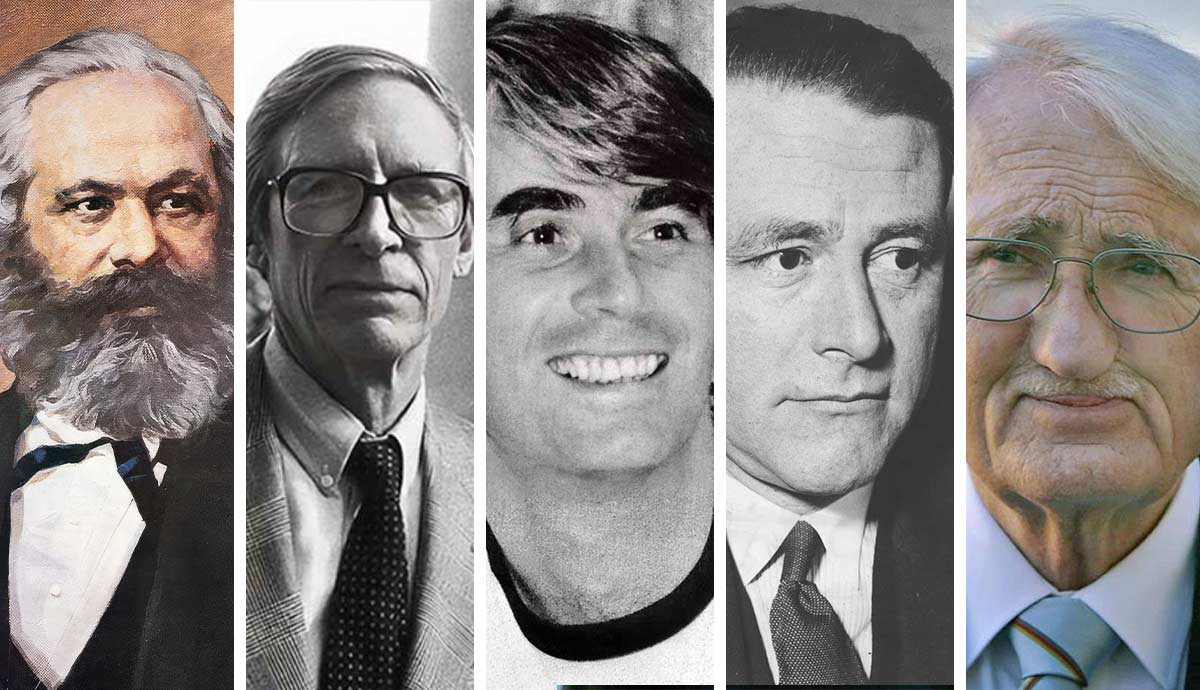

If we are trying to make sense of politics, turning to political theory is a good idea, both in order to gain a more sophisticated vocabulary for speaking about the political and, perhaps, a blueprint for remaking it. This article offers a brief introduction to five influential theorists, whose work continues to exert a substantial influence over contemporary political theory: Karl Marx, John Rawls, Robert Nozick, Carl Schmitt, and Jurgen Habermas.

Crafting a Political Philosophy—An Impossible Task?

Modern political theory can be divided between the Anglophonic (English-speaking) world, and the Continental world, where the dominant languages are French, German, and Italian. The first two political theorists that will be covered in this article are distinctly of the “Anglosphere,” though their work has attracted some limited attention among Continental philosophers, much of which is negative. Nonetheless, the theorists in this article are presented as responsive to one another, because their ideas are.

What do we want from a political theory? Perhaps we want a description of how certain things—certain institutions and practices which we are in the habit of calling “political”—really are. Perhaps we want to know how they should be. Perhaps we want to know how to proceed from the former state to the latter.

There are enormous difficulties with any one person attempting to make such determinations. For one thing, the realm of expertise required must surely encompass many disciplines which are substantial and difficult in their own right: economics, political science, history, various human sciences, and a working knowledge of at least some elements of the hard sciences as well.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

For instance, how can someone theorize about a green energy transition if they don’t know anything about material sciences, engineering, and other disciplines which contain the insight necessary to determine the possible conditions for such a transition? As this article progresses, it is worth asking of each theorist you encounter if and how far they have met this epistemic challenge.

1. Karl Marx: Alienation and Revolution

Karl Marx is known for his theory of history, his analysis of economics, and his call for revolution by the working classes. Where in his work do we find a “political theory”?

In fact, there is no such element; any Marxist theory of politics makes its own judgment about where to cut the joints. The distinctly political insight from which much else in Marx flows is that the status quo—the capitalist system—is neither especially stable nor intrinsically just, but rather relies on the exploitation of the many by a select few.

This is an insight that, in conjunction with the extraordinary breadth of Marx’s writings and their implications, led to the proliferation of Marxist approaches in many disciplines concerned with the study of politics, or adjacent to it. Indeed, almost no intellectual discipline has not developed a significant Marxist tradition.

Yet whether Marxism constitutes a standpoint from which to make political-ethical judgments, whether such a standpoint is even possible in Marx’s work, remains a bone of interpretative contention. Regardless, it is this conception of politics and society which has and continues to inform a vast array of theorizations and reconceptualizations of politics. No theory has proven to be as massive an intellectual and historical force.

2. John Rawls: Liberty and Fairness

John Rawls was a political theorist who spent most of his career at Harvard University. He is known as the liberal theorist par excellence. He, too, appears to offer the possibility of rethinking politics as a whole, yet the purpose of his theory is, in the last analysis, far more modest than Marx’s.

The gist of Rawls’ thought turns around the justification of two political priorities: that of liberty, and that of fairness. These are the two core elements of his theory of justice, in which basic liberties of the kind enshrined in certain constitutions (freedom of speech, assembly, and so on) are defended as a first priority, and the fair distribution of resources is secondary (though still of great importance).

Rawls came up with one of the most famous thought experiments in political theory to explain his conception of the latter, proposing that we should imagine a veil of ignorance that prevents us from knowing where in a given social arrangement we would end up before deciding what that society should look like. The decisions we make from behind this veil would, in Rawls’ view, constitute a fair approximation of how resources ought to be distributed.

The conclusions Rawls draws from this thought experiment rely on the assumption that people evaluate risk in a uniform way, and, more generally, that people desire similar or the same things, really. This strange, flattening assumption is just one of the issues with Rawls’ work. Whatever one’s opinion of the philosophical value of Rawls’ work is almost irrelevant to whether one has to grapple with it, given its ubiquity and deep influence.

3. Robert Nozick: The Individual Against the State

Robert Nozick is best known for his political theory as set out in Anarchy, State and Utopia. This book was a response to Rawls’ A Theory of Justice, the basic elements of which have just been summarized.

Nozick’s main issue with Rawls’ theory is that it proceeds from the assumption that, basic liberties having been secured, the state is free to interfere in society however it wishes to bring about a just distribution. In fact, so Nozick says, what Rawls calls “basic liberties”—those negative, freedoms from the state’s interference—absolutely trump any requirements of just distribution.

Preserving individual liberty requires adopting a very minimal state—one which might prevent violence, fraud, and theft, but does little more than that. Nozick believes that this minimal interference is justified so long as everyone starts from a reasonably equitable starting position.

Of course, Nozick’s minimal state would have to be implemented after vast social changes were instigated first, given that as of now, it is obvious that people do not start with even an approximately equal chance of achieving a good life for themselves. Indeed, the scale of global inequality makes Nozick’s utopian vision particularly distant and difficult to appraise.

4. Carl Schmitt: Friends and Enemies

Carl Schmitt was one of the chief jurists of Nazi Germany, and his theory of politics reflects that in various ways. In contrast to both Nozick and Rawls, Schmitt does not take the primordial moral imperative of the state to be its own negation—that is, the protection of individual liberties.

Indeed, it is exactly this strand in liberal thought that Schmitt thinks to be self-deceptive and, therefore, in need of revision. More specifically, it is the denial of the necessity of the sovereign within a political system, a failure to clearly demarcate sovereignty, that Schmitt objects to.

His most famous political analysis rests on the claim that the essence of politics is the conflict between the friend and the enemy. There is a case to be made that Schmitt’s jurisprudence and theory of politics have everything to do with the fervor with which he took to the Nazi regime in Germany.

Nonetheless, Schmitt’s work has attracted the critical attention of philosophers and theorists from a vast range of political viewpoints, including many on the left, like Antonio Negri and Slavoj Žižek, along with those on the libertarian right, like Friedrich Hayek.

5. Jurgen Habermas: Discourse and Democracy

Habermas’ philosophical interests are extremely diverse and idiosyncratic, as is the manner in which he engages with political and social theory.

At the heart of Habermas’ approach to politics is the conviction that productive communication is possible, and that it is an integral condition to the proper functioning of the political sphere.

His theory of communication and communicative rationality is distinct from previous conceptions of political rationality in that it is characterized as a feature of interpersonal relations, rather than in some way separate from them. Habermas’ perspective on morality is both grounded in existing discursive practices and universal in scope.

Habermas is the only theorist on this list who is still alive, and his work is often seen as a synthesis of many of the intellectual traditions which have come before him, including Marxism and critical theory, pragmatism, Kantianism, poststructuralism, and various others. His work has therefore proven influential among both Anglophonic and Continental philosophers.