How can a philosopher possibly oppose morality itself? Even though it is one of the most infamous elements of Nietzsche’s philosophy, it is difficult not to be struck by the audacity and persistent polemical power of Nietzsche’s moral philosophy when reading The Genealogy of Morals (the work in which morality is dealt with most explicitly).

This article begins with a discussion of Nietzsche’s attitude to morality and its relationship with his attitude toward Christianity. The genealogical method is then introduced, and the two forms of moral paradigm in Nietzsche’s thought as introduced alongside it. This article lastly concludes with a discussion of the relationship between guilt and debt, along with a discussion of how these paired concepts play a role in Nietzsche’s conception of morality.

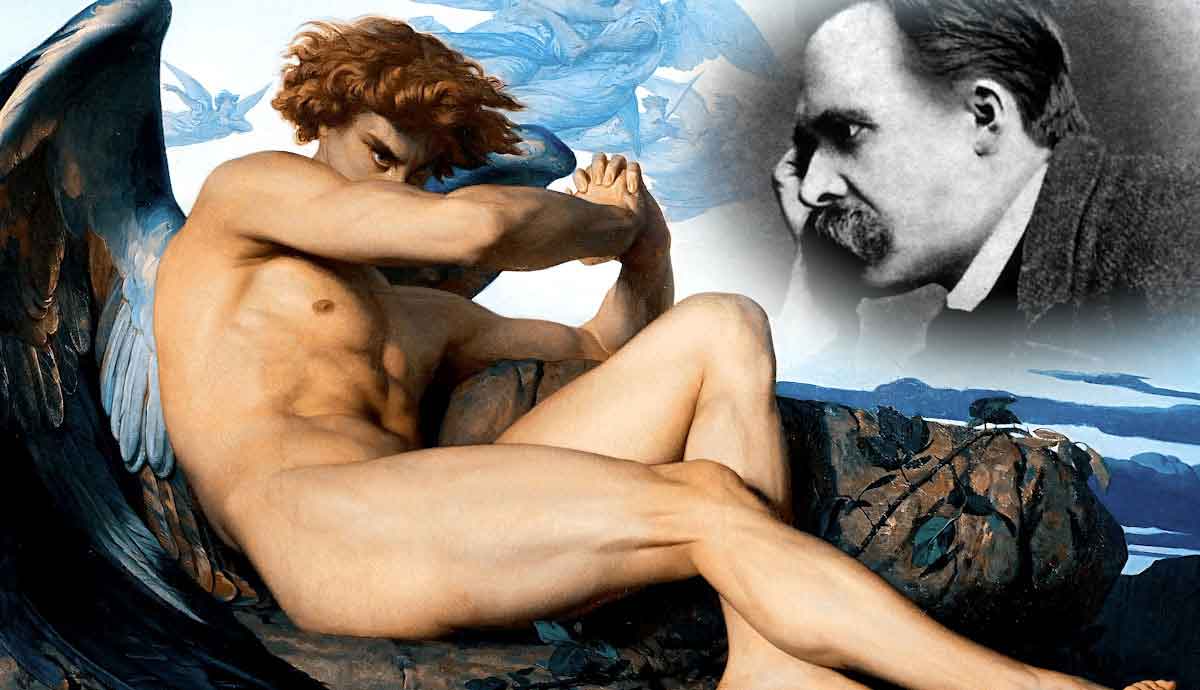

Nietzsche on Morality and Christianity

Nietzsche’s critique of morality is paired with his critical stance toward Christianity. At various points, it is difficult to pin down where Nietzsche’s criticisms constitute a criticism of morality in all of its possible forms, a more specific kind of morality of which Christian, religious moralism, or only the specific kind of morality prevalent in Europe during Nietzsche’s lifetime.

Nietzsche’s skepticism of morality should broadly be understood not as a response to Christian religious morality (or certainly not exclusively), but as a largely secular attempt to rehabilitate and reclaim many of the precepts of Christian morality on the basis of reason.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

The idea that our basic moral commitments are merely in need of an overdue justification, rather than being open to genuine, broad-minded queries, is one of the ideas which Nietzsche was most critical of, which nonetheless appears to prevail today. Just as there is a skeptical element to Nietzsche’s view of morality—in a certain respect, morality is not real—there is also a value judgment being made here.

In other words, Nietzsche thinks that morality is fictitious and our attempts to preserve this fiction are harmful. Nietzsche offers a variety of reasons in support of this claim, but before we can discuss them, it is important to say something about the method which Nietzsche deploys in order to make these arguments. That method is genealogy, one of the most distinctive features of Nietzsche’s philosophical methodology, and also one of the most influential.

Genealogy is the introduction of historical contingency into ideas—it is a denial of necessity on the grounds of historicizing them, by making them the consequence of particular histories. Nietzsche uses this method, in the First Treatise of his On the Genealogy of Morals, to attack what he feels to be one of the most distinctive features of Christian-inspired morality: the belief that morality is at its core about altruism.

The Ethics of Mediterranean Antiquity

The argument rests on another famous Nietzschean distinction: the good-bad versus good-evil dichotomy. This dichotomy represents two ways of conceiving of moral difference, and each is characteristic of a whole ethical approach.

The good-bad version of morality represents, for Nietzsche, the ethical norm of Mediterranean antiquity—that is, of the Greek and Roman periods. What is important to emphasize is that this is a mode of ethical inquiry intractably embedded in the social structure of the Greco-Roman world. That is, goodness begins as a way of describing those of a higher social class, before moving to become a description of characters who embody the “aristocratic” virtues of that social class.

The difference between this version of morality and the good-evil version is that it is focused on violations towards others. Violations of what? Violations of universal prescriptions, ethical or religious laws, which govern the conduct of one person towards another. It is approximately right to distinguish the aristocratic form of ethical life as concerned with virtue.

The Conceit of Evil

The supposed universality of the good-evil distinction, which one might think is a large part of its appeal, is, for Nietzsche, worthy of extreme suspicion. Yet just as the good-bad version of morality can be situated in a distinct historical context—indeed, it must be in order to be understood—so Nietzsche holds that the good-evil version has its own corresponding historical moment.

“Moment” really is the relevant term here. Whereas the aristocratic model of morality is, for Nietzsche, the moral norm of an entire society, the good-evil version of morality comes about with a specific event. This is the so-called “slave revolt in morality,” one of the most famous ideas in Nietzsche’s thought. The basic idea is that the uninhibited, aristocratic leaders of the society in which good-bad morality flourished were able to subjugate (indeed, to literally enslave) those less powerful, both by birth and in character. The consequence on the part of the subjugated was the development of what Nietzsche called ressentiment, which is a special case of the English term “resentment.”

The emphasis here is on the transformative element—the “re” sentiment, feeling again in a different way. The transformative element of ressentiment is the mutation of the feeling of resentment towards those in a position of power to the creation of the concept of evil. That is, they transform an understanding of their social role into a position in a distinctly ethical interaction between the powerful and the non-powerful.

The concept of good in the good-evil version of morality is not the same as the concept of good in the good-bad version. Indeed, given that Nietzsche holds that the good-evil paradigm is determined first of all by the definition of evil, and good is a negation of that conception of evil, the concept of good is totally inverted by the slave rebellion in morality. Nietzsche calls this inversion the “revaluation of values.”

Irrationality in Modern Morality

In other words, the claim of modern morality to a rational basis is ludicrous just because the very ethical prescriptions which we are trying to find a rational basis for are themselves utterly contingent. Indeed, they are a contingency borne of the worst of human emotions—of jealousy at the good fortune of others. Now, let’s point out the obvious.

This all seems rather a tall tale, and certainly an overconfident historical narrativization of what was surely not a single moment (if we are willing to admit this as a change that happened at all). Indeed, Nietzsche’s version of history often reads as a history not of events but of impulses, a kind of internal, psychoanalytic history, which is by its nature only ever hidden and hypothetical. Nietzsche is often quite concerned with the unconscious elements of human life, pre-empting Freud and psychoanalysis.

Following R. Lanier Anderson, there are several features in Nietzsche’s characterization of modern morality which seem to be worth paying especially close attention to insofar as they make his theory of morality seem more plausible. Nietzsche himself observes that there is a telling incongruity in the tendency for a religion like Christianity, which is supposedly built on universal concern and love for all, to lapse into diatribes against the wicked, the sinful, the evil. Indeed, this vengeful tendency goes beyond Christianity as such and appears to be a feature of much so-called moral concern. Moral panics are not exceptional, but rather panic and sentiment seems to be the normal state of morality.

Nietzsche on Morality: Debt and Guilt

The emotional, non-rational elements of moral concern have a tendency to unshackle themselves from any rational boundary that appears to be drawn for them. However, everything we have discussed so far is only half the story, if that! If this is first story and its philosophical consequences constitute one significant part of Nietzsche’s anti-moralism, his theory of guilt and debt is the second part.

Roughly speaking, Nietzsche sees the compensatory element of both guilt and debt as representing another historical relationship. Just as when one is in debt, one must pay what one owes, so too can one accrue a kind of moral debt, which is guilt, and have to find a way to pay back what one owes in a moral sense.

The historical conjecture is this. Debt is basic—debt exists in societies in which the good-bad and the good-evil paradigm exists. At one point, debt existed, and guilt did not. Guilt is borne of debt—it is an internalization of the external fact of being in pecuniary or material debt, just as goodness in the good-bad regime of morality was internalized after having begun as an element of the social hierarchy.

The debt-guilt association functions for Nietzsche both as an explanation of how it is that those at the top of aristocratic societies came to be beholden to ethical precepts which have no place within their system as such, and how it is that moral sentiment comes to be detached from particular acts.

Although guilt begins as denoting a stringent relationship between actions and consequences, action and reaction, when it is taken as a sentiment, guilt has the greatest possible potential to float freely, to become the driver rather than the result of events, and to extend itself far beyond its original terms.

Morality for Nietzsche is not rational, but reactive, and when moral sentiment of the good-evil variety is indulged, one rarely knows how much is too much.