Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582) was a Japanese daimyo who deposed the Ashikaga shogunate and unified 30 of Japan’s 68 provinces through a series of brutal military campaigns from 1568 to 1582. For this, he is known as Japan’s first “Great Unifier,” though his death in 1582 cut his vision short. Japan’s unification was finished over the next two decades by his successors Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu. Oda Nobunaga’s unification effort not only politically and economically reformed Japan, they also transformed Japanese warfare.

Nobunaga: Japan’s First “Great Unifier”

Oda Nobunaga‘s unification campaigns began with his victory over the Saito clan in 1567. A year later, he helped Ashikaga Yoshiaki seize the shogunate by ousting the Rokkaku and Miyoshi clans and taking over Kyoto. At this point, Nobunaga was offered the position of kanrei, deputy shogun, but he refused in favor of grasping total control. He began restricting Shogun Yoshiaki’s powers until he was little more than a puppet and he used him to justify his own conquest of uncooperative clans. Eventually, he exiled Yoshiaki in 1573 and assumed full power.

He appears to have taken personal delight in targeting the Tendai sect of Japanese Buddhists — who held significant political and religious power at the Enryakuji monastery — at the siege of Mount Hiei (1571). The same year, he launched the decade-long Ikkō-ikki campaign by besieging the fortress of Nagashima for the first of three times. The Ikkō-ikki were a Buddhist sect of peasant farmers, Hongan-ji monks, priests, and local nobles who rejected samurai rule. It wasn’t until the third siege attempt in 1574 that he finally eliminated the faction at Nagashima. Numerous conflicts later, the Ikkō -ikki were finally crippled by the surrender of Hongan-ji Temple in 1580.

By 1574, Nobunaga’s forces were such that he could conduct separate campaigns simultaneously. While hunting the Ikkō-ikki, he also eliminated enemy daimyos (feudal lords), one by one. A particularly notable battle occurred at Nagashino (1581), when Oda Nobunaga used firearms to devastate the powerful Takeda clan.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

To mark the peak of his power, his return was greeted by an imperial delegation that offered him the title of shogun. By 1582, Nobunaga had successfully consolidated central Japan and he was planning to finish the effort by invading the east and west. But, while staying at the Honnō-ji temple in Kyoto when most of his army were away reinforcing Toyotomi Hideyoshi, his general Akechi Mitsuhide betrayed him for unknown reasons. Nobunaga was surrounded and injured, and his bodyguard was overwhelmed and killed. With the temple burning around him, he committed seppuku rather than surrender.

Weaponry Innovations: The Introduction of Firearms

Oda Nobunaga changed Japanese warfare primarily through his impressive innovations that spanned everything from weaponry to unit deployment to tactics. Perhaps most importantly, he was among the first to recognize the advantages of guns — particularly, the matchlock and harquebus, the latter of which was introduced to Japan in 1543 by Portuguese traders. When a young man in 1549, Nobunaga armed 500 warriors with matchlock muskets. He later imported saltpeter to produce gunpowder and he established manufacturing centers for artillery, ammunition, and cannons. While cannons were already being used by pirates, Nobunaga was the first to transition to using them on land. He was also the first to use them on a large scale for both offense and defense.

These innovations in firepower can be seen in any of his campaigns after 1570, which all largely centered around the strategic use of firearms. For example, he used cannons to aid the third siege against Nagashima (1574), which he blockaded from both land and sea. The seaborne cannons continually bombarded Nagashima’s watchtowers, allowing Nobunaga’s land forces to conduct a three-pronged attack that forced the defenders into the inner outposts, which Nobunaga then set ablaze.

Military Reforms: A Professional Army

Oda Nobunaga also replaced the cavalry (who were traditionally armed with bows and swords) using the ashigaru as regular troops instead. Ashigaru were traditionally peasant foot soldiers, but he armed them with long spears and either guns or bows. He organized the ashigaru into units and trained them until they were adept at group maneuvers.

This adaptation alone transitioned Japanese warfare away from individual hand-to-hand tactics, towards disciplined group movements, while also beginning the shift away from the samurai as the sole military class. By making the ashigaru regular troops, he gave them the status of full-time soldiers. To supplement this new level of group solidarity, Oda Nobunaga introduced distinctive uniforms to foster an esprit de corps among his red and black troops.

In the Battle of Nagashino (1581), Oda Nobunaga is said to have ordered his newly-created professional army to fire by rank — one of the three lines would shoot, while the others ducked and reloaded to create a steady rain of fire. If true, then this innovation placed him ahead of European armies, who wouldn’t adopt this practice until decades later, in the Thirty Years War, during the Reformation. The method was especially effective against the Takeda cavalry armor. Nobunaga positioned his 3,000 matchlock troops behind wooden palisades and systematically obliterated the Takeda cavalry’s charges, slaughtering some 10,000 and breaking the strength of the major clan’s power.

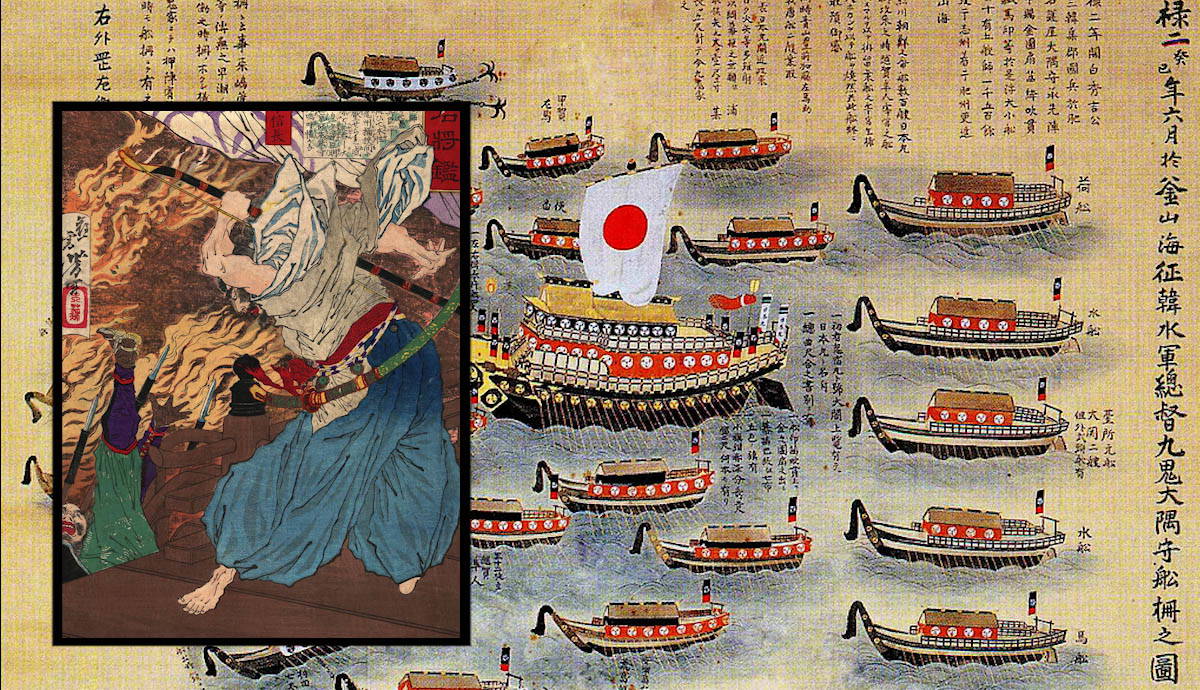

Naval Additions: Floating Fortresses

Less utilized but no less impressive, Oda Nobunaga experimented with iron-plated warships in his personal navy. In 1578, he had six massive atakebune built. While the best were called tekkōsen, which literally means “iron ships,” it is unlikely that they were made with iron. Instead, they were probably reinforced with iron plates to ward off artillery and arrow fire. Still, these warships represented Japan’s state-of-the-art weapons technology, complete with cannons and large-caliber harquebuses.

Nobunaga successfully used these warships to blockade not only Nagashima, but also the Kizu River during the Hongan-ji siege. The first blockade in 1576 was conducted with regular wooden vessels and was broken by the Mōri clan’s superior naval expertise. But, Nobunaga unleashed the tekkōsen for the second blockade in 1578. He sank several Mōri vessels, broke Hongan-ji’s supply lines, and forced its surrender.

The ships were innovative not only in their iron content but also in their deployment. Japanese naval combat traditionally unfolded as hand-to-hand combat between the ships’ crews, but the introduction of the cannon transformed the iron ships into a kind of floating fortress that could easily decimate the enemy’s wooden vessels. While these ships had faults (they were hindered by their size and oar propulsion, and were limited to coastal action) they were nonetheless an impressive advance in technology that expanded the repertoire of Japanese warfare.

Administrative Organization: Daimyos Reorganized

Oda Nobunaga constructed castles in strategic locations in his newly-conquered territories to consolidate control and establish lines of communication. He built roads between these castles to facilitate trade. The roads also increased his army’s mobility, even after reducing his cavalry. A skilled administer, he was innovative in granting positions to his vassals based on merit rather than family or rank. His organizational system was later adopted by his successor, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who infused it into the structure of the famous Tokugawa shogunate. Oda Nobunaga was able to optimize both his organizational structures and his road systems to enhance his army’s mobility.

For forces under his direct command, he could bolster their numbers by recruiting local samurai and ashigaru. Elsewhere, he could rely upon his retainers to act in his absence, with good opportunities for reinforcement if needed. This is demonstrated by the multiple simultaneous campaigns that he and his generals conducted after 1574.

Effective Execution: Ruthlessly Ambitious Action

Though notable in themselves, the successes of Oda Nobunaga’s innovations were even more impressive when combined with his style of warfare. In almost every case, he took the offensive. The enemy army marked his center of gravity, and he sought to kill the enemy daimyo to “cut the head off the snake.” Though it may sound overly simplistic, this approach was prudent in an era when daimyos personally led their own armies and were not permitted by honor to surrender. Additionally, Nobunaga was masterfully cunning and used ambushes, exploitation, and misdirection to devastating effect. He generally preferred to only attack with a superior force and extensive planning.

Oda Nobunaga is well known — though not much admired — for his brutal ruthlessness in battle. He pursued fugitives without compassion and regularly killed defeated enemies. Against the monks, the bloodshed reached massacre levels as he hunted down and slaughtered between 20,000 and 30,000 warrior monks from Mt. Hiei (1571). Here, his army surrounded the mountain cloister, set it on fire, and slowly tightened the noose while killing everyone in their path. Similarly, at Nagashima, he trapped 20,000 locals in the fort compound and starved them before finally burning them alive. In other cases, he took thousands of locals into slavery and killed people indiscriminately. While these methods are less than commendable, Nobunaga’s uncompromising military domination is an undeniable factor behind his success as Japan’s first “Great Unifier.”

The Secret Behind Oda Nobunaga’s Success

While there are of course many factors involved in a campaign’s success or failure, Oda Nobunaga’s swift embrace of burgeoning technologies gave him immense advantages over his enemies. By transforming his peasant fighters into permanent soldiers, he dramatically expanded his fighting capacity. In supporting these greater numbers with domestically-manufactured firearms, he single handedly contributed to the decline of cavalry in Japan in favor of a new professional army. By absorbing supportive daimyo into his merit system while eradicating all daimyo who resisted, he fortified the loyalty of his vassals and ended the fractured feudal age. He proved to be a talented administrator, using his skill to effectively consolidate control over the areas he conquered. His success in unifying half of Japan also directly contributed to the subsequent period of political stability, economic advances, and military consolidation.