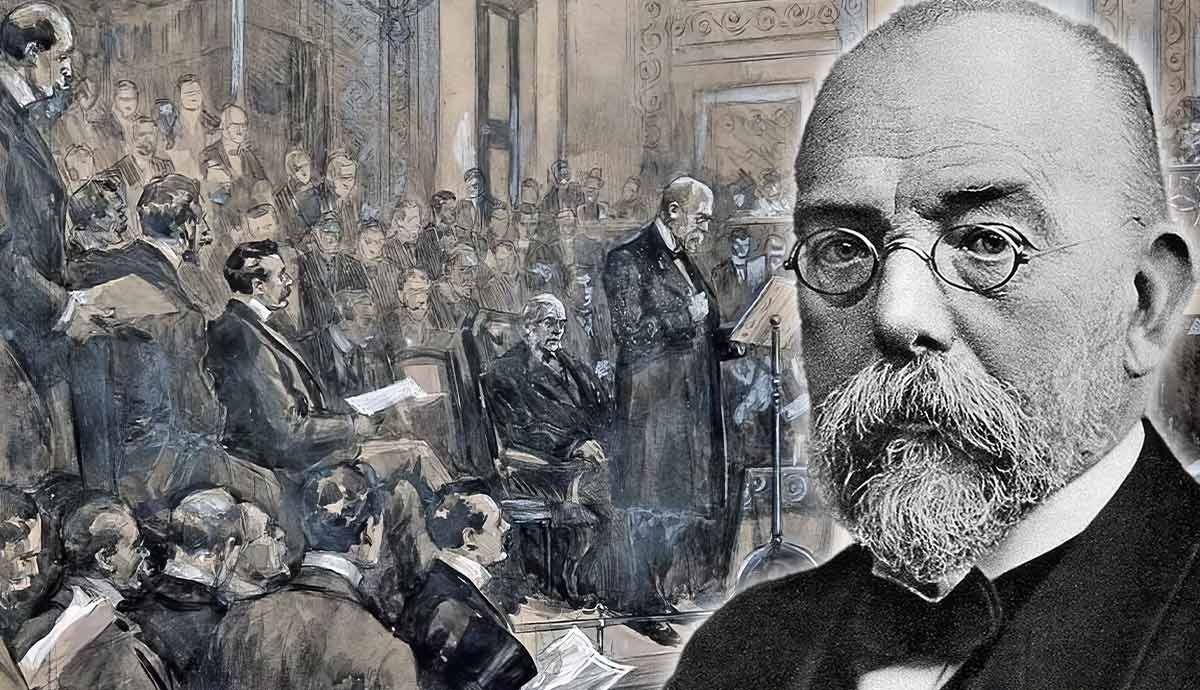

Robert Koch has become famous across the world for his medical achievements. While there is no doubt that he made a considerable contribution to the development of modern medicine, there is also a darker side to his research. Read on to learn more about his career highlights and some of his more questionable decisions.

Robert Koch’s Early Life and Early Career

Robert Koch was born in December 1843 in Germany and was the third of thirteen children born to parents Hermann Koch and Mathilde Julie Henriette. Legend has it that his future academic achievements were foreshadowed when, aged just five, he taught himself to read using his parents’ newspapers.

It was at high school, however, that Koch discovered the passion that would drive his career for the next couple of decades, and in 1862, he enrolled at the University of Göttingen to study medicine.

At Göttingen, he encountered the influential Jacob Henle, a professor of anatomy who, in 1840, had argued that microorganisms caused diseases. Today, we know this theory to be true, but at the time, this was a new theory, and this association probably influenced Koch’s future work.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

In 1866, Koch finished his degree and went to Berlin, where he lived for six months. He continued his research before he obtained a job at the General Hospital in Hamburg. He then worked at a general practice in Hamburg and then at a general practice in Posen, where he completed his District Medical Officer’s Examination. Then in 1867, he married his childhood friend, Emmy Fraatz.

In 1870, his medical career was interrupted when he signed up to serve in the Franco-Prussian War. Upon his return in 1872, he spent two years as District Medical Officer for Wollstein and began the groundbreaking research that would define his career.

Koch Encounters Anthrax

In the late 17th century, anthrax was causing a serious concern due to the number of deaths it was causing, not just among humans but among animals too. Anthrax is a severe infectious disease that occurs naturally in the soil. Humans become affected when they come into contact with an infected animal or contaminated animal products.

Symptoms are largely flu-like, to begin with. Then they seem to fade for a few days before returning, developing into severe lung problems that cause difficulty breathing and shock.

While the bacteria (anthrax bacillus) responsible for the disease had been discovered by scientists before Koch’s research, it had not been scientifically proven as the cause of the disease. So, in his four-bedroom flat, which doubled as a lab, Koch set about scientifically proving the cause of anthrax.

During this research, Koch also managed to prove that, as other scientists had argued but not proven, anthrax was transmitted through infected blood. He used two groups of mice, one of which he inoculated with blood from farm animals that had died from the disease, and another which he injected with the blood of healthy farm animals that did not have the disease.

When the former all died and the latter all survived, Koch was able to prove that anthrax was, in fact, transmitted through blood.

During his research, Koch also discovered the dormant stage of the pathogen, which enabled him to explain the disease’s chain of infection and its resistance to environmental factors. By doing so, Koch was also able to prove that a microorganism was responsible for the disease.

Koch took his findings to Ferdinand Cohn and Julius Friedrich Cohnhiem, who were both impressed by his work and who, in 1876, published his work in the botanical journal and boosted Koch to stardom.

Koch and Tuberculosis

After his fight against anthrax in 1880, Koch was given a job as a member of the Imperial Health Bureau in Berlin, where he moved with his wife and their daughter, Gertrud. With the post, he was given a better lab and some assistants.

At the new lab, Koch began researching a particularly devastating disease: tuberculosis (TB). TB, a serious bacterial infection that affects the lungs, had spread widely, and in Germany alone, it was responsible for the death of one-seventh of the population. Yet, despite the destruction it caused, the reason for the spread of TB had never been uncovered.

After just two years of research, Koch announced at the Berlin Institute of Physiology that he had discovered the TB pathogen: tubercle bacillus. He held a lecture on the Aetiology of Tuberculosis and then published his work.

In 1905, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for the discovery.

Koch’s Research into Cholera

After his research into TB, Koch began work on a disease that had been occupying the minds of many scientists at the time: cholera. Transferred by infected water and with diarrhea-like symptoms, the disease had spread around the world at alarming rates and was causing chaos in the city slums of Europe.

In late 1883, Koch, alongside a team of his researchers, was sent to India and Africa to research the disease. At the beginning of the following year, he identified Vibrio cholerae, the bacteria responsible for the disease.

Upon his return to Germany, Koch was able to apply what he had learned about cholera elsewhere to his own country. He devised rules to control its outbreaks, which the Dresden government approved in 1893. In fact, these new rules were so influential that they still influence disease control today.

Although he was celebrated, both at the time and now, for his discovery of Vibrio cholerae, Koch was not solely responsible for it. The pathogen had already been identified by an Italian anatomist named Filippo Pacini; however, his work did not gain much traction and was largely forgotten in Koch’s time. It is, therefore, possible that Koch was simply unaware of Pacini’s research.

A Return to TB

In 1885, Koch was offered the job of Professor of Hygiene at the University of Berlin, where he also established the Institute of Hygiene. He continued his research with a growing number of students and staff, and the institute quickly became an integral part of the scientific community.

For much of his time working in bacteriology, cholera remained an integral part of his research, but at this point, Koch turned his attention back to TB. He aimed to find ways to contain the spread of such diseases and, in an ideal world, prevent them from existing in the first place.

He began developing a substance called “tuberculin,” made from the bacteria responsible for TB and injected into the patient. He thought the method was successful and took his findings to the Tenth International Medical Congress in Berlin in 1890.

Desperate for a cure for this horrendous disease, Congress accepted Koch’s “cure” despite its risks and side effects. Because of his success, in 1891, the Prussian government built Koch, the Royal Prussian Institute for Infectious Diseases. This was to be one of the world’s first biomedical research institutes.

Travel and Tropical Diseases

In 1896, Koch broadened his geographical scope once more and turned his attention to South Africa, where diseases like rinderpest, often also called cattle plague, Texas fever, and East Coast Fever were all causing havoc for livestock owners.

Koch managed to limit the outbreak of rinderpest (a highly infectious viral disease mainly affecting cattle and buffalo) by injecting healthy cattle with bile from the gallbladders of infected animals; however, he could not identify the disease’s cause.

Then, he researched blackwater fever, plague, and surra in Africa and India and published his findings in 1898.

In the early 1900s, he traveled to East Africa and began researching sleeping sickness, or Human African trypanosomiasis. This devastating disease is transmitted by tsetse flies and was commonly confused with malaria. The symptoms included high fevers, headaches, and fatigue, often resulting in death.

The early outbreaks of sleeping sickness between 1896 and 1906 in Uganda and the Congo killed 800,000 people. This caused concern for European colonial powers because it was causing a loss of livestock and workforce.

It was for this reason that Koch was sent to Africa. However, through his attempts to help, he caused considerable harm, which has become known as his darkest chapter.

Koch had been sent to Africa to research cures rather than remain in his German lab because it was the opinion of the European powers that it was “not desirable to test new medications on Europeans” (Source).

In Africa, he set up research camps (also referred to as concentration camps) within which to treat African people suffering from sleeping sickness. The reasoning behind these camps was to prevent the spread of the disease and keep patients isolated from the rest of the population; however, African people were often forced into them against their will and unable to leave.

As well as keeping patients in appalling conditions, Koch was testing extremely harmful substances on them too. He believed that a substance called atoxyl would cure sleeping sickness. However, atoxyl is an organic arsenical compound, meaning that while it suppressed the parasite for a short time, it caused devastating side effects.

Because of this, patients would appear to recover before eventually experiencing a return of their symptoms. Koch theorized that the disease returned because the substance was not strong enough (and not because the arsenic simply suppressed the parasite).

Consequently, despite being aware of the risks, he decided to double the dose of the drug given. By doing this, Koch also increased the amount of arsenic given to patients. Suddenly they began to suffer from increased pain, and some even went blind.

His actions in Africa have, today, led to much controversy. Some historians argue that what he did was inhumane and cruel and that more attention must be given to his actions.

Robert Koch: The Later Years

In his later years, Koch once again turned to TB. He finally concluded that the bacteria responsible for the disease in humans and cows are different, and in 1901 presented his findings to the International Medical Congress on Tuberculosis held in London.

During his later years, Koch was given a number of prizes and medals for his medical achievements and continued to travel to Africa to study diseases like cattle fever.

He passed away in May 1910 in Baden-Baden, aged 67, and left his only daughter Gertrud and his second wife, Hedwig Freiberg, whom he married in 1893 after his marriage with Emma ended the same year.

While Koch made considerable contributions to the field of medicine and was responsible for the establishment of some of its principal institutions, it is also important to draw attention to his questionable and harmful methods.

Even if they were in the pursuit of greater medical understanding, many African people lost their lives because of Koch’s methods. Therefore, while appreciating Koch’s achievements and legacy, we must also acknowledge the harm done.