When we think about ancient Rome, we rarely think about Roman food. So what did the Romans actually eat? Similar to the modern-day inhabitants of the Mediterranean, the Roman diet consisted of olives, dates, legumes of all types, as well as various types of fruit and vegetables. Salt was also quite common and was required for the production of garum, the recipe for which is below. However, the Romans also tended to eat some animals that we would never consider eating today, including peacocks and flamingos. One of the recipes below is for a small furry animal that is considered a pest — to suggest eating it today would be an offence to all things decent. Let’s dig in!

1. Garum, the Lost Secret of Roman Food

No examination of Roman food can begin without an understanding of garum. Garum was a Roman condiment made from fermented, sun-dried fish and used similar to vinegar and soy sauce today. However, it was not a Roman, but a Greek invention which later became popular in Roman territory. Wherever Rome expanded, garum was introduced. Pliny the Elder tells us that Garum Sociorum, “Garum of the Allies,” was typically made in the Iberian Peninsula and was “the most esteemed kind”. According to Pliny and as suggested by some archaeological evidence, there may even have been a Kosher version of garum.

Garum was used for its high salt content and was mixed with other sauces, wine, and oil. Hydrogarum, i.e., garum mixed with water, was provided to Roman soldiers as part of their rations (Toussaint-Saint 2009, 339). Garum had an umami flavor, very different from contemporary Mediterranean food. According to food historian Sally Grainger, who wrote Cooking Apicius: Roman Recipes for Today, “It explodes in the mouth, and you have a long, drawn-out flavor experience, which is really quite remarkable.”

If you are adamant about trying this Roman food recipe at home, be aware that garum production was typically done outdoors, both because of the smell and the need for sun. The mixture would be left to ferment for one to three months.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

Some similar fish sauces exist today. Examples include Worchester Sauce and Colatura di Alici, a sauce made from anchovies on the Amalfi Coast in Italy. Some modern Asian fish sauces such as Vietnam’s nuoc mam, Thailand’s am pla, and Japan’s gyosho are also considered to be similar.

The following extract is from the Geoponica, cited by Jo-Ann Shelton (1998):

“The Bithynians make garum in the following manner. They use sprats, large or small, which are the best to use if available. If sprats are not available, they use anchovies, or a lizard fish or mackerel, or even old allec, or a mixture of all of these. They put this in a trough which is usually used for kneading dough. They add two Italian sextarii of salt to each modius of fish and stir well so that the fish and salt are thoroughly mixed. They let the mixture sit for two or three months, stirring it occasionally with sticks. Then they bottle, seal and store it. Some people also pour two sextarii of old wine into each sextarius of fish.”

2. Disguised Foods: High Dining in Ancient Rome

One of the most interesting texts from antiquity is Petronius’ Satyricon. It is a satire similar in style to a modern novel and set in Ancient Rome. It tells of the adventures of Encolpius and Giton, a slave and his boyfriend. In one famous chapter, Encolpius attends a cena at the house of Trimalchio, a wealthy freedman who accrued his wealth through less than honorable means. A cena, or dinner was often a banquet for the rich and an opportunity to demonstrate ostentatious wealth. At the beginning of this particular banquet, slaves bring out a chicken made of wood, from which is removed what appear to be eggs. Trimalchio however, has tricked his guests, for instead of eggs they receive an elaborate egg-shaped pastry (Petronius, 43).

What we can glean from this text is that one way of demonstrating wealth was to have a cook shape food like other sorts of food. Similar in concept to meat substitutes, yet without any practical purpose. In fact, there are a few recipes like this in De Re Coquinaria, the Roman food cookbook commonly attributed to Apicius. The end of the recipe given below states that “No one at the table will know what he is eating” and it is representative of a cultural idea that would not be considered refined today.

The following excerpt is from De Re Coquinaria:

“Take as many fillets of grilled or poached fish as you need to fill a dish of whatever size you want. Grind together pepper and a little bit of rue. Pour over these a sufficient amount of liquamen and a little bit of olive oil. Add this mixture to the dish of fish fillets, and stir. Fold in raw eggs to bind the mixture together. Gently place on the top of the mixture sea nettles, taking care that they do not combine with the eggs. Set the dish over steam in such a way that the sea nettles do not mix with the eggs. When they are dry, sprinkle with ground pepper and serve. No one at the table will know what he is eating.”

3. Sow’s Womb and Other Spare Parts

Many of the animals which we use for meat today were also used in Roman food. However, rather than the very specific cuts of meat we tend to eat in the contemporary Western World, the Romans ate whatever part of the animal they had available. There even existed a method for making the womb of a sow into an enjoyable meal, in De Re Coquinaria. The Romans also ate the brains of animals, usually lambs, and they even prepared brain sausages.

That’s not to say that culinary habits in Ancient Rome were sustainable. The banquets of the elite were excessive beyond contemporary understanding. Many banquets lasted eight to ten hours, although the night’s proceedings certainly depended on the austerity of the host. Decrying his contemporaries, the satirist Juvenal complains of this excess: “Which of our grandfathers built so many villas, or dined off seven courses, alone?”

The following excerpt is also taken from De Re Coquinaria:

“Entrée’s of Sow’s Matrix are made thus: Crush pepper and cumin with two small heads of leak, peeled, add to this pulp rue, broth [and the sow’s matrix or fresh pork] chop, [or crush in mortar very fine] then add to this [forcemeat] incorporating well pepper grains and [pine] nuts fill the casing and boil in water [with] oil and broth [for seasoning] and a bunch of leeks and dill.”

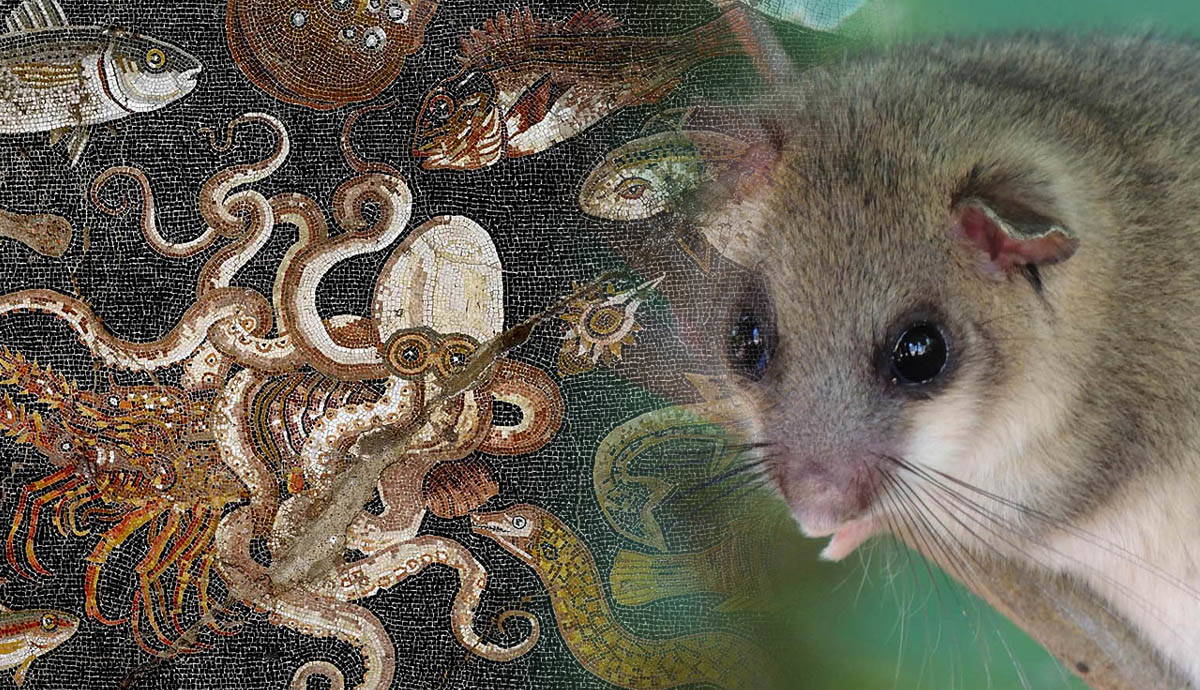

4. Edible Dormouse

While some Roman food may be somewhat appealing and exotic, nothing manages to repulse contemporary scholars of Roman food habits more than the humble dormouse. Edible dormice, or glis, are small animals who live across the European Continent. The English species’ name comes from the fact that Romans ate them as a delicacy. Typically, they were caught in the fall, as they are at their fattest just before hibernation.

Trimalchio’s dinner in the Satyricon, as well as in De Re Coquinaria record that dormice were eaten frequently in ancient Rome. Apicius’ recipe calls for them to be stuffed with other meats, a typical Roman method of food preparation.

“Stuffed Dormouse is stuffed with a forcemeat of Pork and small pieces of dormouse meat trimmings, all pounded with pepper, nuts, laser, broth. Put the Dormouse thus stuffed in an earthen casserole, roast in the oven, or boil it in a stock pot.”

5. Barley Broth, Pap, Porridge, Gruel: Roman Food Eaten by Ordinary People

So far, we have discussed meals from the tables of the Roman elite. While high social status guaranteed access to any variety of food from all over the Empire, those who worked for a living in Ancient Rome made do with simple meals. For most of the history of Roman Civilization, poor people living in Rome had stable access to grain. This was due to the legislative achievements of Publius Clodius Pulcher, who made free grain available to those eligible to receive the “Grain Dole”. Historian Jo-Ann Shelton in her As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook on Roman History states that: “The poorest Romans ate little other than wheat, either crushed or boiled with water to make porridge or puls, or ground into flour and eaten as bread…” (Shelton, 81)

It must be stated that, because most of these recipes come from Apicius, the following recipe is not definitively that of an ordinary Roman. While it could potentially have been, the fact that the source is a book written at an unknown date for a wealthy audience means it is likely that this was a hearty breakfast for a member of the elite or their household. Still, it gives us an insight into the type of cooking done on a day-to-day basis by the most hidden people in the historical record.

“Crush Barley, soaked the day before, well washed, place on the fire to be cooked [in a double boiler] when hot enough add oil, a bunch of dill, dry onion, satury and colocasium to be cooked together for the better juice, add green coriander and a bit of salt; bring it to a boiling point. When done take out a bunch [of dill] and transfer the barley into another kettle to avoid sticking to the bottom and burning, make it liquid [by addition of water, broth, milk] strain into a pot, covering the tops of the colocasia. Next crush pepper, lovage, a little dry flea-bane, cumin and sylphium. Stir it well and add vinegar, reduced must and broth; put it back into the pot, the remaining colocasia finish on a gentle fire.”

Apicius: The Man Behind Our Knowledge of Roman Food

So how do we know anything about Roman food? There are many sources on Roman food, in particular letters of invitation from one literate member of the Roman elite to another. We have some sources of this type from Martial and Pliny the Younger (Shelton, 81-84). However, evidentially the Apicius text, the De Re Coquinaria is the major source on Roman food. So then, who was this Apicius, and what do we know about his book?

There is no definitive proof connecting any author to the text we now attribute to Apicius. One of the surviving manuscripts titles the book as Apicii Epimeles Liber Primus, which translates to The First Book of the Chef Apicius. Interestingly the word “Chef” (Epimeles) is actually a Greek word, indicating that this book may have been translated from Greek. Traditionally it has been attributed to Marcus Gavius Apicius, who was a contemporary of Emperor Tiberius.

This Apicius is also referred to in other texts from Seneca and Pliny the Elder, who probably lived after he died. This man was known as a gourmet of Roman food, the archetypal glutton. However, he is also mentioned in Tacitus’ The Annals, Book 4, in relation to the Roman Prefect Sejanus. Tacitus alleges that Sejanus rose in rank and wealth due to a romantic relationship with the same Apicius. Sejanus’ wife is later referred to as “Apicata”, who some have suggested may have been the daughter of Apicius. (Lindsay, 152)

Due to the presence of recipes named after 3rd century Emperors, such as Commodus, it is impossible to attribute the whole text of De Re Coquinaria to Apicius. Historian Hugh Lindsay highlights that some phrases in the Historia Augusta: Life of Elagabalus reference the Apicius text. Therefore, Lindsay argues the book may have been written before 395CE, assuming that the Historia Augusta was written before that date and could have been the same book mentioned by St. Jerome, the Christian theologian, in a letter of his dated roughly 385CE.

Furthermore, Lindsay (1997) argues that, while it is indeed possible some of these recipes are from the pen of Apicius (in particular the sauces), the whole text should be seen as a compilation of many different materials compiled by an unknown editor.

Regarding the real Apicius, Lindsay (1997, 153) states “How his name came to be associated with the 4th century text which has survived can only be a subject of speculation, but the moralistic stories which were associated with his name, and his outstanding status as an epicure may provide a sufficient explanation.”

Maybe Apicius himself wrote a cookbook that was later expanded upon, or else a writer in the 4th century CE used his famous name to lend authority to their own work. We may never know for certain.

Sources

Carcopino, J. (1991). Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire. London, England: Penguin Books

Petronius. (1960). The Satyricon (W. Arrowsmith Trans.) New York, NY: The New American Library

Juvenal. (1999). The Satires (N. Rudd Trans.) New York, NY: Oxford University Press

Shelton, J. (1998). As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Toussaint-Saint, M. (2009). A History of Food (A. Bell Trans.) New Jersey, NJ: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Apicius. (2009). A History of Dining in Imperial Rome or De Re Coquinara (J. Velling Trans.) Project Gutenberg, August 19 2009. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/29728/29728-h/29728-h.htm#bkii_chiii

Fielder, L. (1990). Rodents as a Food Source, Proceedings of the Fourteenth Vertebrate Pest Conference 1990, 30, 149-155. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/vpc14/30/

Leary, T. (1994). Jews, Fish, Food Laws and The Elder Pliny. Acta Classica, 37, 111-114. Retrieved July 8, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24594356

Pliny the Elder (1855). Naturalis Historia (H. Riley Trans.) The Perseus Catalog, https://catalog.perseus.org/catalog/urn:cts:latinLit:phi0978.phi001

Marchetti, S. (Jul 2020). Did fish sauce in Vietnam come from Ancient Rome via the Silk Road? The similarities between nuoc mam and Roman garum. South China Morning Post.

Lindsay, H. (1997) Who was Apicius? Symbolae Osloenses: Norwegian Journal of Greek and Latin Studies, 72:1, 144-154 Retrieved July 12, 2021 from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00397679708590926