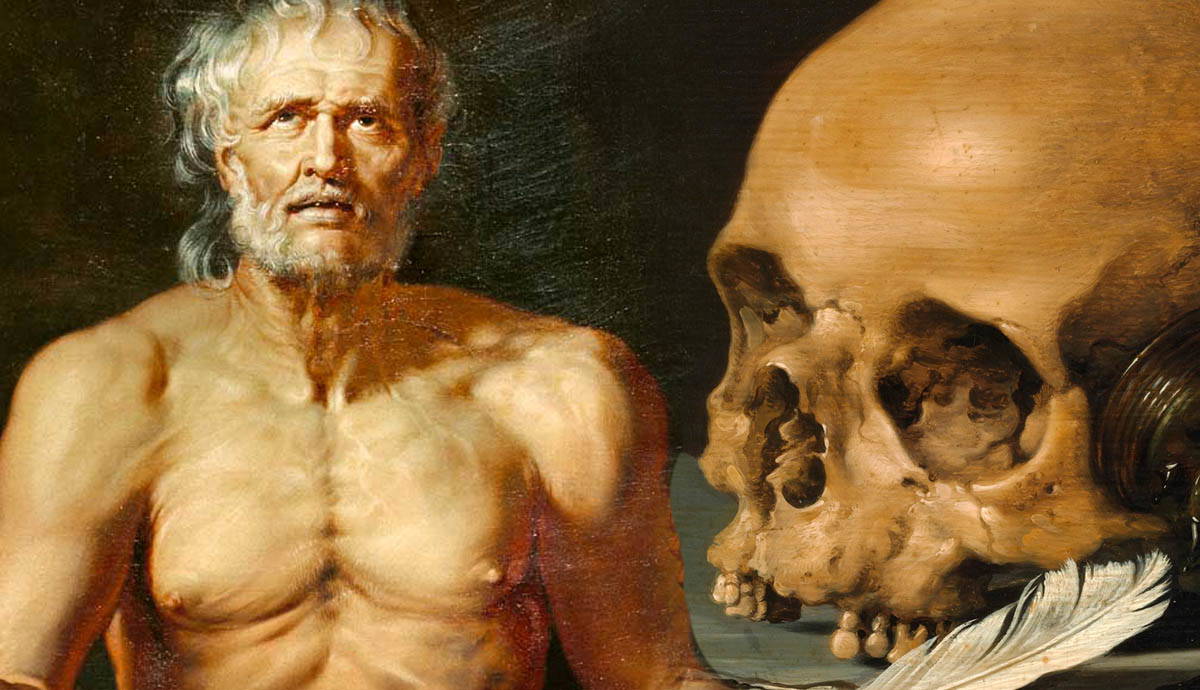

Most people tend to avoid thinking about death and dying. Few things elicit as much anxiety and fear in us as death does. The Stoics had much to say about this anxiety surrounding death. The very thought of perishing makes people uncomfortable, so it’s better to avoid those images that might put you in a foul mood. In this article, you will learn about how the Stoics used thoughts about death as a tool to improve their outlook on life. The thought that one day we will perish, that we won’t be able to eat, love, laugh. It depresses us when we think of the things that we enjoy so much knowing that one day they’ll be stolen from us.

The Fear of Death and Dying According to the Stoics

Nobody in history has been more attuned to the creeping fear of death and dying than the Stoics were. Marcus Aurelius, the most famous Stoic, once said: “Stop whatever you’re doing for a moment and ask yourself: Am I afraid of death because I won’t be able to do this anymore?” (Meditations X, 29). It’s a tough pill to swallow, but it is true: the end will come for all of us. For some, sooner rather than later.

Yet, modern society does not encourage us to contemplate death on a daily basis. We aren’t as exposed to death as our ancestors were. Therefore, we aren’t that equipped in dealing with it when push comes to shove. But we are reminded that death is lurking every time we lose a loved one. It shakes us to our core, and we need many days, weeks, or months, to return to our normal state.

Death as Part of Nature

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly NewsletterYet, accepting death as a part of life, and nature, can set us free and allow us to fully embrace each day as a present that is given to us. The Stoics knew this better than anyone else. They simply accepted life as is and didn’t yearn for more.

The Stoics’ ideal life is one that is in harmony with Nature. They were aware that every one of us is part of nature and that one day we all will return to it. This brought calm to their daily living and indifference to external events, however negative they may be. Stoics were not pursuing wealth or fame, but an excellent mental state. They considered the cultivation of this state to be virtuous and identified it with being rational.

That is why sometimes they could seem superhuman. They cherished the challenges that life brought and tackled them head-on. And, what greater challenge there is than the one of dealing with death? Consider the case of the Stoic philosopher Julius Canus. When Emperor Caligula ordered his death after Canus angered him he simply proclaimed: “Most excellent prince”, and then, “I tender you my thanks.” When a centurion came to take him ten days later, he was found playing a board game.

When Publius Clodius Thrasea Paetus was given the order to commit suicide (a free choice of death, the Romans called it, or liberum mortis arbitrium) he turned to his companions and excused himself. He then went on to invite the quaestor to witness as he slit his veins. Awaiting his death, he chose not to complain nor wallow in pain, as much as he probably felt it. Instead, he discussed with his friend Demetrius the nature of the soul.

Such actions are unimaginable nowadays. Most people would think Canus is unwell in the mind. What person would be in a cheerful spirit when he or she knows that doom awaits them? Well, a Stoic would be.

A Tool for Appreciating the Present

As the Stoics tried to teach us, being aware that you will one day die is an extremely powerful way of finding calm. They knew that by contemplating bad things that can happen to us, we learn to appreciate the things we already have. We come to feel grateful to have another day on this planet.

Only if we remain blind to death, can it have a debilitating effect on us. The Stoics made it their mission to meditate on death and dying daily.

When Stoics contemplate death, they do so not out of a desire to die, but of a desire to get the most “juice” out of life. Knowing that life is finite, they opened their eyes to the simple beauties of it. Death is scary. The unknown is scary. But death could be years or decades away; it could be tomorrow. We simply don’t know when it will knock on our door.

And, if we don’t know then why bother our minds with thoughts that bring us nothing but misery? Isn’t it better to be joyful knowing that life has granted us this day and to use it to the fullest?

Stoics believed that death wasn’t the cause of misery for most people, but that the fear of dying itself brought misery. But, where other people saw chaos, they saw an opportunity for growth. They not only didn’t avoid contemplating death, they actively fantasized about it.

One of the most famous Stoic philosophers, Epictetus, once said:

“I must die, must I? If at once, then I am dying: if soon, I dine now, as it is time for dinner, and afterwards when the time comes I will die.”

Or consider Seneca’s view that “A man cannot live well if he knows not how to die well.”

Death Is Not Under Our Control

Epictetus has left us with the Dichotomy of Control. He believed that some things are in our control, and some things aren’t. He derived that most of the unhappiness is caused by mulling over things that we can’t control, or thinking that we can control them.

It’s not things that upset us, said Epictetus, but how we think about things. Our judgments on things bring us misery, not the things themselves. That is a crucial lesson imparted by the Stoics. If we judge that something is bad, we will associate that thing with negative feelings.

Now, every time we think about that a cloud will loom over our minds and make us feel unproductive thoughts. A life in which we solely focus on the things that we can control is a life of progress, a life of happiness.

A life in which we focus on the things we can’t control is a recipe for a miserable life. The sooner we come to terms with this the better. Truth is, bad things happen and will happen. We will get sick, we will get hurt and the weather will ruin our plans for the day. As the Stoics stressed, these things are simply out of our control.

What Can We Control?

Things happen, and how we see them can completely change our relationship to life. And, our relationship to death as part of nature.

Even though things that we have complete control over aren’t that numerous, the one thing that is under our control is our mind. More precisely, how we judge the things that happen to us.

One of the most memorable Stoic concepts is “Memento mori” translating to “remember that you will die”. It’s a simple practice that you can do each day. By remembering that you will one day die, you will enjoy life’s treasures more.

You’ll be more grateful for the simple things, the sun shining on your face, the shared laughs and the luscious meals.

In his book “Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals” Oliver Burkeman offers us a glimpse into what he calls “Cosmic Insignificance Therapy”. It’s eerily similar to what the Stoics are teaching us. We often expect wonderful things to happen all of the time, and we’re disappointed when things don’t go in our way.

We set the bar too high. We’re unsatisfied if we don’t do work that will last for countless generations. Everything must achieve a purpose, and feed our efforts to transition to the next thing, and then the next. We’re in a rat race and our opponent is ourselves.

In doing so we disregard the mundane, but profound things. If we pay attention to them and immerse ourselves at the moment we won’t feel the urge to escape it. He says:

“dropping back down from godlike fantasies of cosmic significance into the experience of life as it concretely, finitely—and often enough, marvelously—really is.”

Being a Stoic: Remembering That We’re Mortal

It’s a wonderful reminder that in the grand scheme of things our death will be insignificant. We are part of the soil, and we’ll return to it in time. Best to make use of our time in ways that will bring us happiness and meaning. Not misery.

When my next training session arrives, I won’t lose myself thinking that one day I won’t have the capacity to practice. Instead, I’ll cherish the fact that I had the opportunity to do it in the first place.