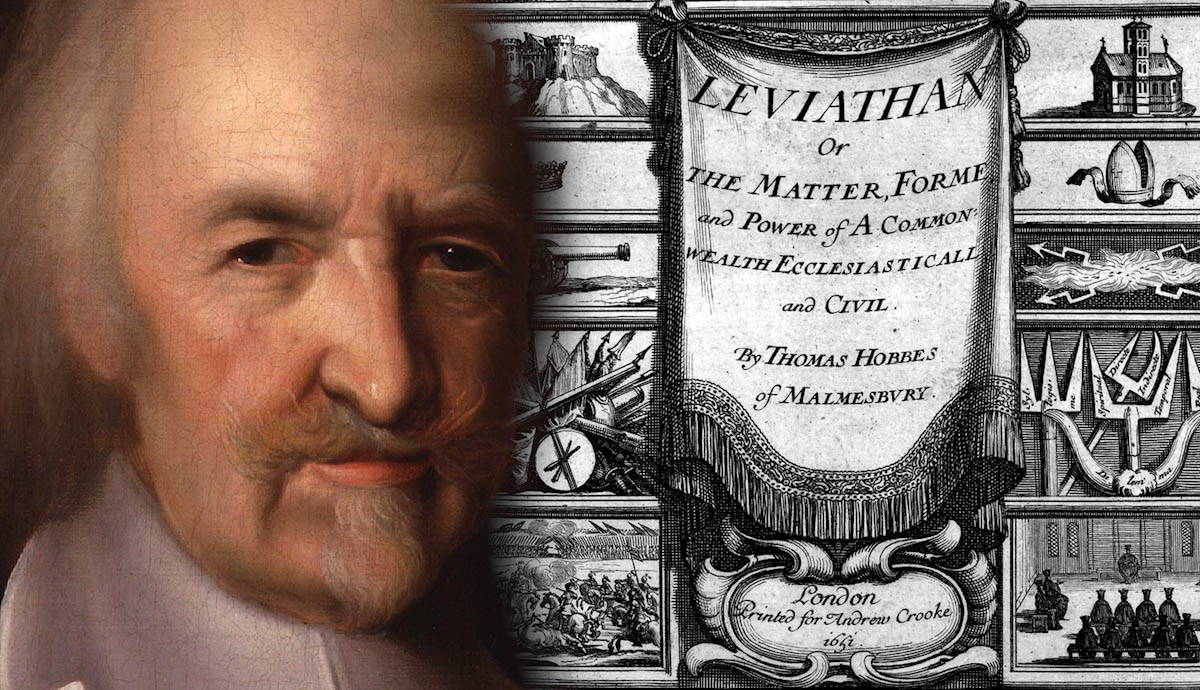

Wrought with the pressure of a transforming political climate, Thomas Hobbes’ philosophy rocketed him to fame after he penned his work Leviathan. He wrote in a generation moulded by the political violence not only of the Thirty Years’ War on the European continent, but also of the English Civil War on his home turf. The religious-political violence of this era ultimately shaped modern statecraft and political theory as we know it today. And yet, though the proceeding generation was unabashedly opposed to authority (bringing a few revolutions to fruition with them), Thomas Hobbes was different.

The Thirty Years’ War

The decades preceding the publication of Leviathan are those that influenced it. Since the era of Martin Luther, significant tension between Protestants and Catholics rippled through northern and central Europe.

These tensions ultimately boiled over and manifested in the Thirty Years War, which raged from 1618 to 1648. Protestants and Catholics violently clashed; the ideological differences between the two branches of Christianity being both modesty and control.

Catholicism adhered to a structured hierarchy of society that was dominated by the Pope in Rome. Protestantism upheld a more introspective means of worship focused on the relationship between the individual and the divine. Fundamentally, the conflict came down to control. Whether Catholic or Protestant, the Thirty Years’ War birthed modern state operations as we know it today.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly NewsletterThat is where Thomas Hobbes comes in. Having spent his formative years surrounded by conflict (both continental during his time in France and domestic at home in England) Thomas Hobbes decided to write a philosophical treatise about governmental control.

His work would go on to inspire and influence—both in agreement and refutation—dozens of fellow political theorists, both contemporary and later on.

The State of Nature

Arguably, the most influential idea that came from Hobbes’ pen was that of the State of Nature. Hobbes held a cynical opinion about human nature, claiming that human beings are naturally solipsistic and dangerous. Famously, Thomas Hobbes was a very paranoid, fearful, and careful man.

In support of his point, Thomas Hobbes cited his fictional State of Nature—a hypothetical time and place devoid of political establishment or social construct. In the State of Nature, every human being exists as a hunter-gatherer as animals do. In this state, Hobbes argues, people will stop at nothing to sustain their own survival: it was, quite literally, every man for himself.

Thomas Hobbes famously claimed that life in the State of Nature would be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Above anything, Hobbes feared death; his entire political axiom stemmed from doing everything in one’s power to prevent an untimely death before the “Maker” would have it by nature.

Because the State of Nature is so dangerous and frightening, among many other adjectives, Hobbes claimed that we had to make a covenant. The covenant is a promise humankind made with God where, in exchange for complete and total protection and sheltering, humankind would give up (some of) its natural rights: an eye for an eye. The political equivalent of this covenant between humans and God became the relationship between citizen and ruler.

God and Government

In his notion of the covenant, Thomas Hobbes merges the role of the secular king with the role of the sacerdotal God, blurring the lines between monarch and divine. In fact, he advocates that the secular king always has the best intentions for his people in mind, while no other authority can adequately perform in that way.

While religious folk pray to God for protection, Hobbes turns to his secular king for protection from his greatest fear; while religious folk look for answers from this God to live well, Hobbes interprets political manifestations from the king (the law) as a means to living well. For Hobbes, the monarch’s very word is law, and all should submit to it in order to live long and live well.

For Thomas Hobbes, politics should orient itself against early death. Any action a monarch can take is for his best interests and it is within Hobbes’ philosophy to submit without question. Looking at historical examples, Hobbes would argue that the political ideas of monstrosities such as Adolf Hitler or Joseph Stalin were ultimately for the best interests of their people, were he alive during their tenures.

Hobbes, Philosophy and Religion

In his philosophy, Thomas Hobbes was a stalwart materialist. As such, he gave no power whatsoever to idealistic philosophies invented in the mind—if it did not exist for one to perceive empirically, it simply does not exist at all. Though logically sound, this thinking could easily lead one into trouble in the Catholic-dominated seventeenth century.

Hobbes affixed the simple definition “matter in motion” to his perception of the universe. Every facet of life is simply different masses of matter riding the flux of time and space which is sustained by an “Unmoved Mover.” This, coupled with his materialist philosophy, is closely related to Aristotelian thought.

Seeing as the Hobbesian philosophical positions are often political in nature, it becomes the responsibility of the ruler to protect the people—the covenant. Hobbes was much more fearful of physical suffering inflicted on his body over spiritual suffering inflicted on his soul: the authority of the ruler quite literally eclipses the authority of God. Religious and secular authority becomes conflated. In his philosophy Hobbes affixes a material body (the King) to God—simultaneously denying God in the Christian sense.

This was considered outright and inherently blasphemous. As a result, Leviathan was banned in England and Thomas Hobbes was almost tried by the Church—much like his contemporary and friend Galileo Galilei—were it not for direct protection from the King of England (Hobbes’ former pupil). A neat metaphor for Hobbes’ idea for a king, isn’t it?

The Legacy of Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes expounded a political philosophy unique for its time. In an era where swaths of the European continent revolted against oppressive authority, Hobbes advocated for submission. The true virtue of his thought is simply longevity and safety; doing whatever is necessary (including foregoing natural rights) in order to obtain these.

Hobbes lived a long life even by modern standards, passing away after bladder issues and a stroke at the age of 91. Was his longevity due to his fearful, paranoid, and careful nature? More importantly, is a longer, safer life with diminished political rights worth living?