Contrapposto is an Italian, art historical term meaning ‘counterpoise.’ The term is most often applied to a pose in classical and Renaissance art, in which a standing person balances their weight on one leg, so their opposite hip rises on a diagonal axis to create a natural curvature. This stance became particularly popular during the 14th to 18th centuries as it conveyed dynamism and movement, or an air of relaxed ease. Some of the first instances of the Contrapposto pose can be traced back to the Kouros sculptures of ancient Greece, in which artists sought to move beyond the stiff, upright stance of earlier human sculptures. During the Renaissance period, artists revived this classical stance for a new era, and they adopted the term ‘Contrapposto.’

Over the next few centuries, the pose continued to appear in both painting and sculpture, as artists experimented with making more elaborate and sophisticated variations on the theme. During the 19th century, the overtly stylized nature of the Contrapposto stance became less common, although modern and contemporary artists have sometimes made references to it as a nod to the history of art. Below are some of the most revered examples of Contrapposto from throughout art history.

1. Doryphoros (Spear Bearer), by Polykleitos, 450-440 BCE

Doryphoros (or Spear Bearer) is one of the most celebrated sculptures of classical antiquity. This life-sized, standing male nude was carved by the Greek sculptor Polykleitos, a prominent figure during the 5th century BCE. As well as epitomizing the idealized male nude, with carefully balanced bodily proportions, the sculpture also demonstrates early use of the Contrapposto pose, which gives the male nude a naturalistic posture, as if caught mid-moment.

2. Hermes Carrying the Infant Dionysus, by Praxiteles, 4th century

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly NewsletterThis marble sculpture, believed to be by the revered ancient Greek artist Praxiteles, tells the story of Hermes and the infant child Dionysus. We see how Hermes leans his weight back onto his right leg, causing his hips to angle downwards in a relaxed demeanor, encapsulating the Contrapposto stance. Meanwhile his shoulders angle in the opposite direction, creating dynamism and movement.

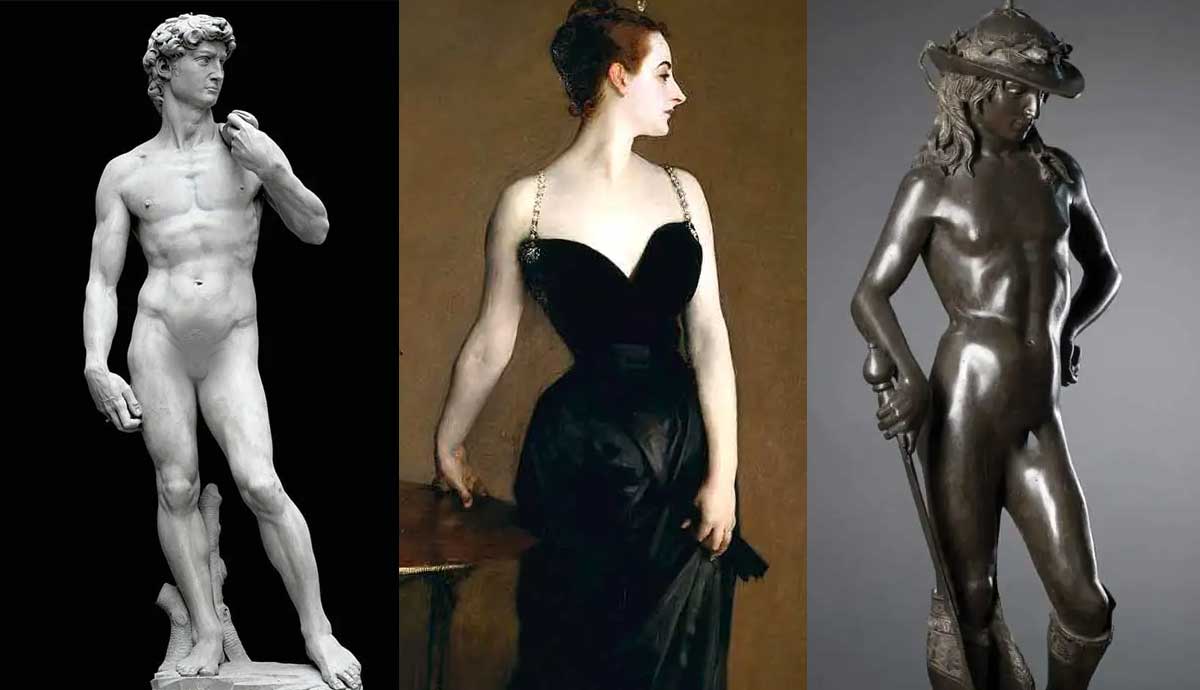

3. David, by Donatello, 1425-1430

Donatello’s statue of the Biblical David holds a significant place in art history, as the first full nude sculpture to be made since antiquity. In this striking, near full-sized male nude, Donatello demonstrates his awareness of classical traditions, reviving the Contrapposto stance for a new era. His take on the posture is more exaggerated than in earlier, ancient sculptures, with David’s front leg jutting far forward while he leans back onto the other. This, combined with the hand on the hip, gives David an air of confident nonchalance, capturing the cheeky, irreverent spirit of this unlikely hero.

4. The Birth of Venus, by Sandro Botticelli, 1485-1486

In Sandro Botticelli’s timeless depiction of The Birth of Venus, painted between 1485 and 1486, the Italian Renaissance painter captures the goddess of love as she emerges from a clam shell in the ocean. Botticelli creates the sensation of movement in Venus’s body by arranging her into a subtle Contrapposto, with weight held back in her left leg while the other is angled just in front. Sandro Botticelli further elevates this quality of energy and movement through fluttering drapes and fine strands of hair blowing in the breeze.

5. David, by Michelangelo, 1501-4

Building on Donatello’s legacy, Michelangelo made it his mission to great a superior David of colossal proportions, who represented the epitome of male, idealized beauty. While Donatello employed the Contrapposto stance to convey cheeky irreverence, in Michelangelo’s version, the pose is enacted to give his subject an air of defiant, unshakeable confidence. Michelangelo’s David leans back on his right leg, bringing his hips sloping downward from right to left, while his broad shoulders follow the opposite axis, tilting downwards from left to right. This twisted stance, along with pushed back shoulders and raised head, gives David an assured ease, as he prepares himself for the battle ahead.

6. The Three Graces, by Antonio Canova, 1815-17

The Three Graces is a masterwork in the career of Italian Neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova, defining his innate ability to create breathability and humanity in marble. This particular group sculpture demonstrates the growing sophistication in the use of Contrapposto in art, as each female figure in this group of three is positioned in a variation of the pose, leaning on one leg with the front one bent. He carefully angles their bodies so they appear to move symbiotically in harmony with one another, suspended mid-motion for all time.

7. Portrait of Madame X, by John Singer Sargent, 1884

While the use of Contrapposto poses became less popular in the 19th and 20th centuries, some artists did look back to the classical tradition, reviving it in their own distinctive ways. Leading 19th century portrait painter John Singer Sargent adopted a Contrapposto pose for his scandalous Portrait of Madame X in 1884. We see how her hips and shoulders are angled in opposite directions, giving her a haughty, seductive quality.