Cubism was one of the most radical movements of the modernist era, challenging us to understand art in an entirely new way. Spearheaded by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in early 20th century Paris, Cubism broke apart pictorial conventions, replacing single point perspective with radical, multiple viewpoints. Their aim was to reflect the way the human eye really sees the world, not as a static, complete picture, but as a prismatic and constantly moving experience. The Cubist movement is usually divided by art historians into two main areas – Analytical Cubism, (1908-12) and Synthetic Cubism (1912-1914). So, what, exactly, is Analytical Cubism, and how do we recognize it?

Analytical Cubism Was the First Phase of Cubism

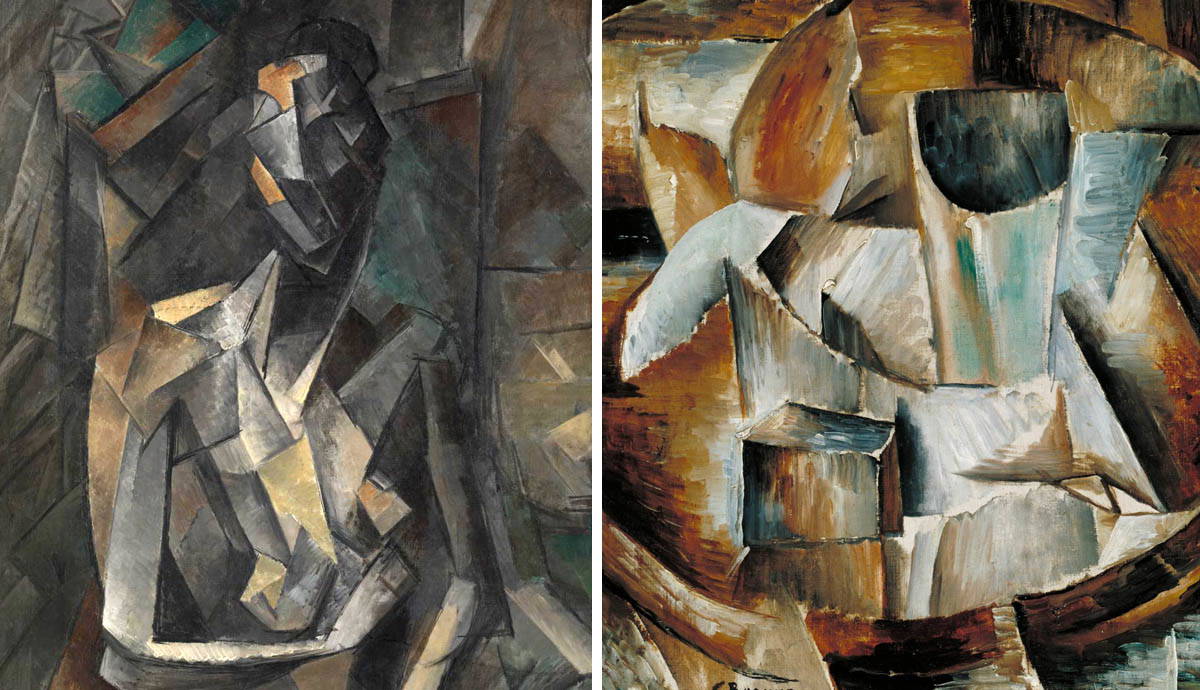

Analytical Cubism is the phrase used to describe early Cubist art. Art historians have noticed how Cubist art made between 1908-12 had a distinct look to it that was different from later phases of the style. They noted the ‘analytical’ way early Cubists interpreted reality, taking a structured, dissected view. Instead of attempting to recreate a single viewpoint, they looked at objects from varying viewpoints and attempted to combine a series of conflicting angles into a single, flat image. The result was a fragmented image featuring multiple viewpoints and intersecting planes. In many early Cubist paintings we see bottles from one angle, guitars from another, and so on.

The leading artists associated with this phase of Cubism were Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, who worked so closely side by side that it is sometimes difficult to tell their work apart. Spanish painter Juan Gris and French artist Jean Metzinger were also associated with Analytical Cubism, although their work is often more distinguishable from that of Picasso and Braque.

This Analytical Approach Was Influenced by Paul Cezanne

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly NewsletterPost-Impressionist painter Paul Cezanne is often referred to as the father of modern art, and this may be because his art had such a profound influence on the advent of Cubism. It was Cezanne’s flat, faceted forms that really excited the early Cubists, because they broke reality into a series of angular components. Cezanne also demonstrated elements of multiple perspective in his art, in an attempt to grasp the ungraspable chasm between his eye and the real world beyond it. His late ‘Montagne Saint Victoire’ series demonstrates this process masterfully. The faceted, geometric nature of early Cubist art also took inspiration from African art, which was being imported into Parisian museum collections during this time.

Analytical Cubism Focused on Still Life

Although their world view was entirely fresh and radical, the Analytical Cubists stuck with some pretty traditional subjects, usually still life (although the occasional portrait and landscape popped up now and again). They did this deliberately, so they could focus their attention on static, simple objects, and really get in there and analyze them from above, below and all around. That’s why you see a lot of guitars, bottles, fruit and tables in this early Cubist phase.

Their Compositions Are Often Busy in the Center

Interestingly, art historians have observed how the compositions in many early Cubist paintings tend to get busier and more complex towards the center of the image. It is this activity that really pulls the eye in, like the eye of the storm, while there is less going on all around it. George Braque’s Bottle and Fishes, 1910-12 shows how effective this experimental technique was in creating a lively and engaging image.

Analytical Cubism Was Usually Muted in Color

One hallmark feature of Analytical Cubism was muted, pared back colors, usually in shades of grey, brown, black and dark green. The artists chose these color schemes so the viewer wouldn’t get distracted from the main focus, which was the structured complexity of the composition. Working with simpler colors must also have made life easier too, giving these artists free reign to home in on creating dizzyingly complex designs that continue to amaze and fascinate audiences today.